As a youngster this was always among my preferred stories, both because it showed a 12-year-old Jesus going off on His own, stressing out His parents the way I always did mine, and then having an impact, intellectually, with adults.

It was more than that, of course, but back then, as a child, I was struck by the confirmation that kids might have a place in the greater scheme of things, and that even though we didn’t have the power of Divine inspiration, God could speak through a young person on matters of importance. Young people mattered, and they had a voice.

Clearly the depth of the liturgical moment was lost on me and there is so much else to understand about this passage of the Bible. But my childhood delight in this story wasn’t completely wrong either. And it’s especially relevant in the context of education.

Jesus is listening to the elders of the church, but also asking questions, even advancing new knowledge. Here is Jesus boldly interrogating the established tradition and communicating deep truths in a context where He was unquestionably underestimated. This in an environment where He would normally be dismissed, taken for granted or expected to be silent. I would like to think that, despite His divinity, it took courage and incredible self-belief to do what He did.

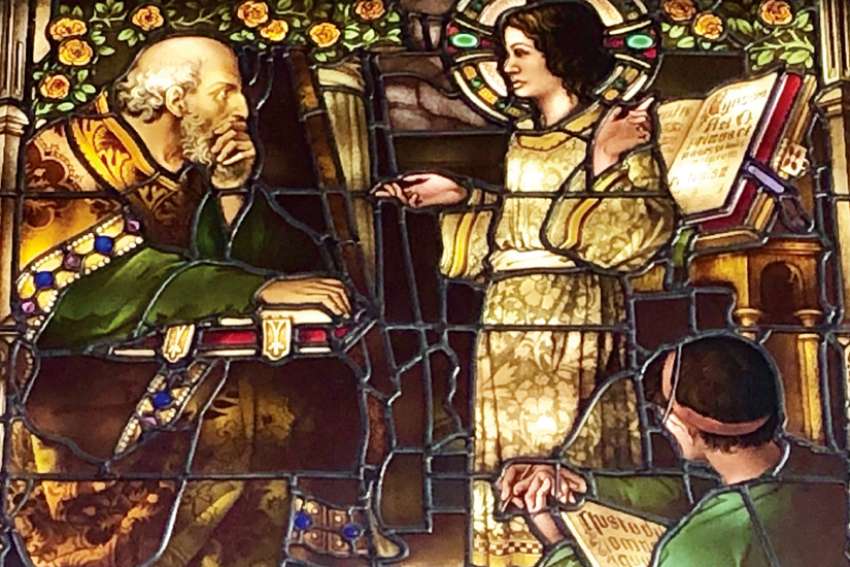

There is another important aspect of this lovely story. In re-reading Luke, we can see that the child Jesus is in conversation with the rabbis. Here is the Christ child initiating what we might now call a Socratic dialogue. And here are the rabbis modelling good teaching, listening to and valuing the opinions of the child. Here, more than ever, is a powerful story that teachers can and must remember to learn from their charges — that learning is a two-way street.

In a speech to our incoming Education students, I used this example to frame their anticipated journey. I discussed the extraordinary gift that their future profession lays out for them, but one that will not be without its challenges and hurdles. I noted that there would be days when they would feel entirely unprepared for what they had to do, “when you will feel more like a cop than a teacher, an exhausted guardian rather than an inspired motivator.”

But the reality is that the work they will be doing, if it’s fed from the heart, has the potential to transform and uplift like few other professions in this world. Their students will represent all aspects of society and they will need love, inspiration, discipline and humour.

The students may feign disinterest while secretly marvelling at the world the teachers are opening up for them — even though they might not be able to tell them that in the moment because it wouldn’t be cool. They will find, as I did, that the letters of thanks come years, sometimes even decades, later by students who were inspired by them but who have only just put the pieces together.

The reality, of course, is that prospective student teachers need to be prepared for the classroom, mind, body and spirit. They need to have real-world experience, but also a wide context to understand the diversity of experience they will face.

It is the job of a university to do just that: to offer depth and breadth, context and meaning, the chance to succeed and even at times to fail. Of all things, perhaps compassion is the most important thing for all teachers to take into their classrooms because we live now, more than ever, in a wounded world.

As a consequence of this preparation, though, when they go out into the real world they will be amazing: in their knowledge, in their passion for ideas and in what they are prepared to give back to their students and their community. It will be important for them to identify some strong role models early on so that they have a base of reference — especially when the going gets tough.

To my mind there can be no role model more inspirational than the child in that stained glass window. When our new teachers do get into the classroom, they should do what Jesus did in His — speak truth to power, challenge established ideas, understand the rules but not follow them blindly and inflexibly, and inspire people to look at the world through a different lens, with heart, with passion and with commitment.

If they do that, their success is guaranteed.

(Turcotte is president of St. Mary’s University in Calgary.)