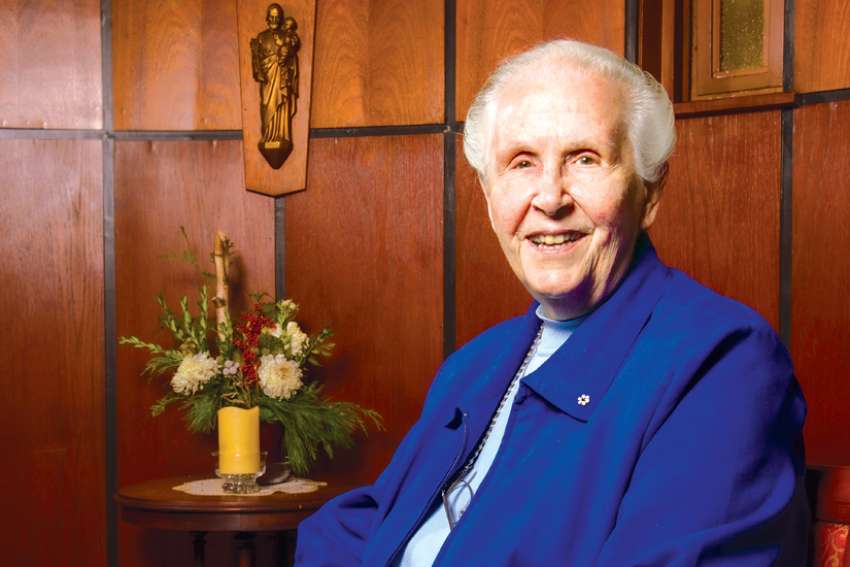

By giving the Order of Canada to Sr. Sue Mosteller of the Sisters of St. Joseph, the country is in fact elevating both her quiet accomplishments and the ideals that drive her, whether that means a better life for those with intellectual disabilities or a life of meaning for young people.

She is one of 120 Canadians this year either named to the Order of Canada or promoted within its three ranks. In the annual New Year’s list, the 86-year-old was named to the middle rank of Officers of the order, just below Companions and above Members.

The award’s citation reads: “For her dedication to improving the lives of people with intellectual disabilities, and for her decades of work as a leader of L’Arche.”

“Everybody who was involved with nominating Sue talked about this combination of her great capacity — intelligence, organizational skills, her deep humanity and her incredible capacity to listen, to be there with people,” said L’Arche Toronto outreach officer John Guido. “She wasn’t from on high. She was from the group; she led from the group as a collaborator.”

No date has been set for when Mosteller will be formally awarded her medal by Governor General Julie Payette.

Mosteller was born in Ohio to Canadian parents in 1933 and came to the University of Toronto to get her degree in English literature. While studying, she boarded with the Sisters of St. Joseph and by the time she graduated was ready to join in their life.

After vows, she taught school in British Columbia and Ontario. In her early 30s, she made a pilgrimage to Lourdes and heard Jean Vanier speak at St. Michael’s College about L’Arche and living with the disabled. She went to the Mother Superior and asked whether she might try living with the young L’Arche Daybreak community established in 1969 on farm land north of Richmond Hill, Ont.

Mother Superior said no. She needed her bright young sisters in classrooms. Mosteller went back to teaching Grade 3. But the idea of L’Arche, Vanier’s vision of community, wouldn’t leave her alone.

“It was funny, because I didn’t know people with disabilities,” Mosteller recalled. “But there was this attraction to this new kind of endeavour.”

In the early 1970s the Second Vatican Council had washed ashore in the Canadian Church. Religious sisters who had spent their lives living behind the locked doors of institutions and keeping them running — schools, hospitals, parishes — were stepping out and rediscovering their vocations in the world, not separate from it.

Mosteller recalls how much the Council opened up religious life.

“It wasn’t just me alone. It was rampant in our congregational lives,” she said. “Sisters were already starting food kitchens and things like that. It was so radical that you can’t even describe what life was then.”

The sisters had long provided services to the poor and the marginalized. Living with the poor, sharing their lives on an equal footing, was no small change.

“The whole thing with L’Arche that turned my head around was that I was the one who was transformed,” said Mosteller.

In 1972 Mosteller again went to her superior with a request to live in L’Arche.

“She said, ‘Let’s pray about it.’ ”

Three days later Mosteller had permission and that urging of her heart was suddenly a reality she had to face.

“Truly, I didn’t know anything. I didn’t know anything about taking care of people. I didn’t know people with disabilities at the time,” she said. “The funny thing is, the minute I walked in the door I was responsible for this house of 26 people. First thing I got was the government regulations on all the things that had to be taken care of.”

By 1976, Mosteller’s good sense was evident to such an extent that she was elected the second International Co-ordinator of L’Arche, taking over from Vanier. During her nine years travelling the world and encouraging communication between L’Arche communities, the network expanded from 30 to 65 countries.

It was during the second half of her 40 years spent living in L’Arche that the real revolution in the organization began.

Vanier had begun L’Arche in 1964 under the guidance of his Dominican spiritual director. The first L’Arche in North America, L’Arche Daybreak in Richmond Hill, was started by Anglicans Ann and Steve Newroth. Through the 1970s L’Arche remained an experiment in a Christian laboratory. But in the 1980s, as L’Arche expanded into non-Christian countries and people of other faiths came to live in L’Arche, it was time to ask how this experiment would live on in a more diverse world.

“We weren’t there to make people into Catholics at all. We were there to respect who they were and to try to help them grow,” said Mosteller.

But how? Mosteller knew a priest who could tackle the question — Fr. Henri Nouwen.

“Henri, he had a gift for it and he knew how to do it. He could show us the gift that we had in this diversity,” she said.

By 1986 Nouwen was living at Daybreak and working with Mosteller. In those years he went from psychologist, university professor and public intellectual to the author of The Return of the Prodigal Son.

Today Mosteller is his literary executrix, responsible for getting the Henri Nouwen Society off the ground and setting up the Henri J.M. Nouwen Archives and Research Collection at St. Michael’s College.

She is more than muse to one of the most popular and influential Catholic authors of the past 50 years. Mosteller has published three of her own books, beginning with My Brother, My Sister in 1972, then A Place To Hold My Shaky Heart: Reflections From Life In Community in 1998 and Light Through The Crack: Life After Loss in 2006.

Guido remembers first meeting Mosteller as a 23-year-old who had arrived at L’Arche full of fears and doubts and misgivings. This older, religious woman told him he could contribute.

“Her sense is that every person is gifted. She radically believes that,” Guido said.

Thirty years on, Guido finds himself in awe of how this 86-year-old is involving herself in the lives of millennials, acting as consultant to Sacred Design Labs — an American experiment in spiritual life for people who have little or no attachment to religious tradition.

“Her real life still comes from the connection with young people,” Guido said. “When she is with people with disabilities, the relationships are so deep and so strong. But the real call for her is to continue to nurture a new generation, and to name where the Spirit is working in the world, in their lives.”

For Mosteller, being interviewed and photographed and honoured and praised is uncomfortable. After three clicks of the shutter and an adjustment to the lights, she figures the portrait session is done and she wants out.

“There is literally no one on Earth who would scorn honours as much as Sue Mosteller would,” Guido said.

But Guido is certain Canada needs to take note of Mosteller. “She’s so fundamentally Canadian,” he said.

Mosteller believes in her country.

“Any country that takes care of people who have difficulty taking care of themselves in such a beautiful way, where everybody is transformed — not just the people who have the fragility, but everybody in their own fragility is transformed — that’s a great, great asset to a country,” she said.

Guido hopes more people come to know Mosteller for “this incredible combination of being a pastoral leader but also a fellow traveller on the road to Emmaus — always there with us. I just think that’s her gift and the beauty of her life.”