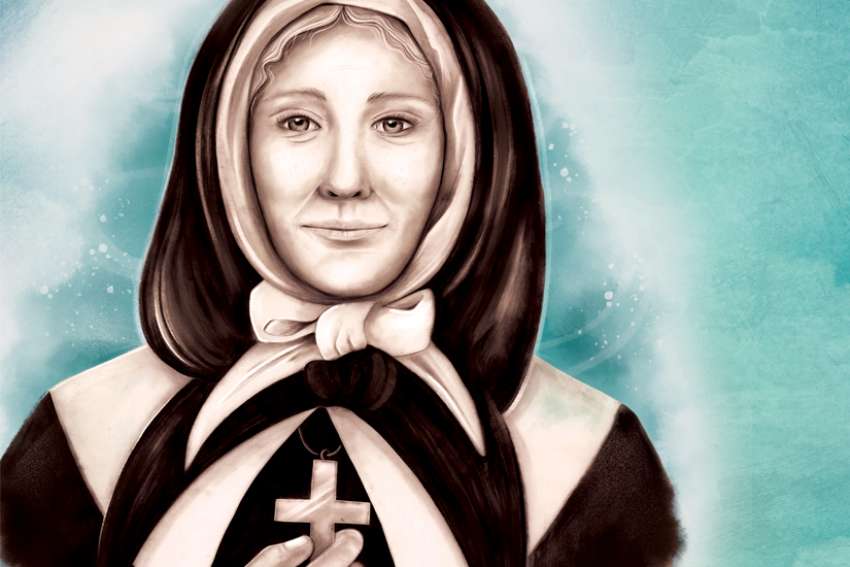

Not when that woman is Marguerite Bourgeoys, a woman who crossed an ocean and was instrumental in planting the seeds that would see the small community of Ville-Marie on an island in the middle of the mighty St. Lawrence develop into the metropolis that has become Montreal. The founder of the Congregation of Notre Dame in Canada was a woman who took charge and made things happen, rarely taking no for an answer as she established a religious order and the French colony’s first school while working alongside pioneers Jeanne Mance and Paul de Maisonneuve in developing this new world community.

“In a sense, she was very much about people and relationship, which is a feminist in the very best sense,” said Kidd, a Notre Dame sister.

This year, Bourgeoys, who was canonized by Pope John Paul II on Oct. 31, 1982 as Canada’s first female saint, is being honoured by her congregation to mark 400 years since her birth on April 17, 1620 in Troyes, France. Her pioneering efforts in what was to become Canada helped create a new society and a religious congregation that has spread to seven other nations.

It was a radical approach Bourgeoys brought to this new land, especially for a woman, when she arrived in Ville-Marie at age 33 in November 1653. She was an educator, an evangelizer and a proponent of conciliation with the Native peoples. Her path followed the footsteps of Mary, who young Marguerite developed a devotion to through a spiritual experience during a procession in honour of Our Lady of the Rosary.

“I found myself so moved and so changed that I no longer recognized myself,” we learn from The Writings of Marguerite Bourgeoys, a book published by the congregation in 1976.

Like Mary, Bourgeoys wished to participate in the founding of a society with the same ideals as the first Christian community.

“She had a vision. You know, as much as people wanted her kind of cloistered and contained, well certainly (Bishop Francois Laval) did, she really wanted to be with people,” said Kidd.

As circumstance would have it, it wasn’t always a given that Bourgeoys was going to have such an effect on what would become Canada. The sixth of 12 children raised in a deeply religious French home, she “sought to know God’s will for her” through prayer and chose to turn her life over to God by entering a cloistered order of sisters in France, writes Sr. Sheila Sullivan in a biography of her order’s founder.

She applied to a Carmelite convent, but was turned down. She then tried to join another cloistered community in Troyes, but was again rejected.

“For Marguerite, this was a period of confusion and uncertainty about her future,” said Sullivan.

But where one door closes, another opens.

“Her spiritual director at the time said maybe what’s not possible in France is possible in New France,” said Kidd, campus minister at the University of Prince Edward Island in Charlottetown.

Around this time Bourgeoys met de Maisonneuve, governor of Ville-Marie, whose sister Mother Louise Chomedey was a member of the Congregation of Notre Dame in Troyes. Bourgeoys learned of the difficulties and hardships in the colony, and set in motion a new venture for herself.

“De Maisonneuve was in need of a teacher for the young French children of Ville-Marie, and Marguerite was searching to know what God wished her to do with her life,” said Sullivan. “When de Maisonneuve invited Marguerite to come to Ville-Marie to assume responsibility for education in the colony, it seemed like an answer to Marguerite’s prayer.”

Despite the objections of her family, who thought it foolish to abandon her home for the unknown of this faraway colony, Bourgeoys was determined to set off on her pioneer life, where she would be met with hardships, physical, spiritual and emotional. Loneliness, isolation and fear of attack from the Iroquois were only some of the troubles associated with this outpost.

But Bourgeoys would persevere.

“She came to Ville-Marie to teach but began by providing as many services as she could in order to respond to the needs of the colony,” said Stephanie Manseau, director of communications with the Congregation of Notre Dame in Montreal.

Bourgeoys welcomed and gave a temporary home to the Filles du Roi, female wards of French King Louis XIV who were sent to New France to be the future wives of men in the colony. Bourgeoys’ role in helping the young women earned her the title “Mother of the Colony.”

She had the famous cross atop Mount Royal re-erected and built Notre-Dame-de-Bon-Secours, Montreal’s first stone chapel. The first school, offering free education to both boys and girls, finally opened in 1658, and the next year she returned to France to recruit companions who would form the core of the Congregation of Notre Dame (which was independent of the order in France. It was only 1981 that the orders would reconnect, said Kidd).

Bourgeoys “understood food for body and soul,” said Kidd.

“She didn’t Christianize with the cross, she did it with people and with food and education. The new evangelization is some of our jargon of this day. But Marguerite knew what it was to evangelize by witness moreso than by word,” said Kidd.

"...Marguerite knew what it was to evangelize by witness moreso than by word."

Perhaps that could be an example today in Canada as the nation struggles to reconcile with our Indigenous neighbours. It was something she was able to do in her time.

“In the 1670s, 1680s, we had First Nations’ women joining the congregation. That’s unheard of,” she said.

Three-and-a-half centuries later, those who followed in her shoes have stayed true to Bourgeoys’ example.

“We’re called to be on the peripheries, on the margins, and that’s a good thing for us,” said Kidd.

Catholic education is probably where the congregation has made its greatest mark, “and it’s the foundation that we stand upon,” said Kidd. But Bourgeoys’ legacy and that of the sisters is so much more than that.

“Marguerite responded to the unmet needs of her time. So that’s the call for us as her daughters today, to respond to the unmet needs of our time,” said Kidd. “There’s some pretty neat things happening that just keeps her legacy alive.”

She sees this in her own calling now as a spiritual animator on a secular campus. Or in the work of Sr. Nancy Downing, a lawyer who has for years worked on issues of homelessness, poverty, fair housing and civil rights and is now executive director of Covenant House New York, which cares for youth who call the streets home.

“It’s really how do we use the gifts and talents we have individually to help people be free,” said Kidd.

Nowhere is this more evident than in, ironically, Bourgeoys’ home of Quebec. It’s a province that has taken secularism to the extremes, where Bill 21 has enshrined a respect for the “laicity of the State.” Yet St. Marguerite Bourgeoys’ example remains influential, in the schools and parishes throughout Quebec (and beyond) that bear her name, where witness does the talking, said Kidd.

“In our community we have drop-in centres and after-school programs, those kind of things. It’s the spirit of Marguerite.”

Sullivan says her example of caring for the common good is needed today more than ever.

“The difficulties we face are different from the ones Marguerite encountered, but the demands for love, self-sacrifice, courage, faith and hope are the same,” she said. “Who better to help us in our struggles to create a more humane world that this pioneer woman of Ville-Marie, St. Marguerite Bourgeoys of Canada?”

The 400th anniversary of Bourgeoys’ birth has been a shot in the arm for the congregation, which has been marking the occasion over the past year. But since the calendar turned to 2020, and especially since her feast day on Jan. 12, celebrations have been ramping up.

A number of events are planned, many in Troyes, and in Canadian communities where the congregation is active. These include concerts, Masses, a pilgrimage to Troyes and the opening May 7 of a new permanent exhibition at the Marguerite Bourgeoys Museum in Montreal (see margueritebourgeoys400.org).