Journalists generally believe in a just world. In the natural, proper order of things the weak should be protected and the truth spoken. So when truth has been obscured or the powerful have abused the weak, journalists scream. The greater the violation, the louder the scream.

In a sense, journalism serves the same purpose as pain. Your doctor needs to know, “Where does it hurt?” Pain tells the story. Without pain there’s no diagnosis.

But journalists aren’t doctors. We identify problems but don’t fix them. Government, the legal system, Church leaders hold that power, acting for and with the people they serve.

Journalism is part of our collective process of discernment. It begins by distinguishing between what’s true and what’s not. Then it asks what’s important and what’s not. Finally, it combines the true and the important into a story. Once a story is told, the process of discernment is handed off to readers.

The people I met in Nova Scotia crave exactly that kind of discernment. They want it now.

“I’m old and I know I’m going to go soon,” Gerry Donovan told me. “We don’t have much time. I have this thing in my head, it’s just rattling in my head, that God’s in a hurry. He wants to do something.”

As a member of a team that traversed Antigonish after Bishop Raymond Lahey was arrested, Terry O’Toole told me that just trying to do something for victims, even victims outside of the class-action suit that will cost Antigonish $18 million, was a sign of hope. The diocese has offered 10 free counselling sessions for anyone who has suffered an assault.

“There were people who were very, very glad that (offer) was there,” said O’Toole. He said many other victims could have joined the settlement process but knew that $10,000 wouldn’t heal their deep pain. “A lot of them felt some fixing up inside had to happen before they were going to feel good as Catholics again – and as human beings.”

The best journalism is an encounter with other people in which a reporter becomes a conduit into other lives, other realities. But journalism can’t transform that encounter into communion. For that you need the Church.

Communion, however, is not necessarily a comfortable, affirming, familiar place.

“You know, the Church isn’t about family ties,” Archbishop Anthony Mancini told me. “The Church is about ties with the Lord that even supersede that which is familial. Brothers and sisters in the Lord have to become phrases that take on a whole lot more meaning and a whole new understanding.”

I hate this story because it is never complete. True, it no longer hits a wall of denial or insulting attempts to minimize its significance (insulting to victims, not to journalists). But although there is finally a willingness to examine causes, everybody is too eager to find a simple, final answer.

The only things that can save us are truth in the spirit, the spirit in our prayers, and hope born from humility. If we can find those, the next child victim may never happen. But we won’t have life in the spirit without discernment – constant, ongoing discernment.

I hate this story now. I will love this story if you’ve read it with an open heart, with charity and hope, and use it in your own discernment, in your own prayer, and share it so that the Church can discern forever and ever, world without end. Amen.

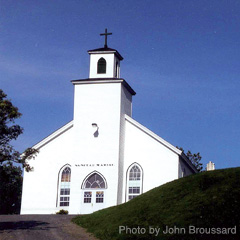

| A shattered church seeks faith and hope Nova Scotians recovering from crisis |

||||||

|