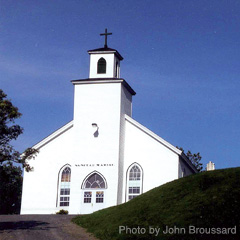

>ANTIGONISH, N.S. - On April 13 the little wooden church on the hill overlooking Maryvale burned down. Located in the diocese of Antigonish, it was a mission church — one of four churches served by the priest in Lakevale. St. Mary’s was insured, but the insurance won’t fully pay to replace the 150-year-old structure.

A pretty good case can be made that the diocese needs that insurance money more than the people in Maryvale need another church. The diocese of Antigonish, comprising Cape Breton and three counties in Northeastern Nova Scotia, must raise $18 million to compensate victims of clerical abuse. If St. Mary’s is not rebuilt, Maryvale Catholics only have a 15-minute drive to Georgeville for Mass on Sunday. Yet the parish has decided to rebuild.

In their resolve, they resemble the broader Catholic community in Nova Scotia that is working to rebuild a shattered Church.

“There’s tremendous symbolism in that building,” said parishioner Terry O’Toole. “The diocese has been hurt. The parish has lost its church. But now there are people who can’t do enough for the building committee, the fundraising committee and the parish council. That crisis has really created opportunity.”

The rebuilding committee has raised $25,150 but the most significant achievement is that Maryvale Catholics understand what that church has meant to them — and what it could mean in the future, said O’Toole. Parishioners envision a multi-purpose building with services for seniors and young people, a place where the community can gather for everything from meetings to dances, said O’Toole. He calls the new church “more of an all-encompassing building.”

+ + +

The Church in Nova Scotia is changing because the Church in Nova Scotia has changed. It’s been painful, and nobody is saying the future will be any less so. In the next year or so the diocese of Yarmouth will cease to exist. After Halifax absorbs Yarmouth, it will take seven hours to drive from one end of the archdiocese to the other. In the next two years the diocese of Antigonish will almost certainly have far fewer parishes. It will very certainly have fewer priests, fewer properties and less money. It already has fewer parishioners.

The few, however, are determined they will have a future.

Clerical sex abuse will have cost Antigonish $18 million by Nov. 2012. That’s when the diocese pays the last of three installments to settle a class-action arising from sexual assaults attributed to the deceased Fr. Hugh Vincent MacDonald. The class action claimed for “systemic negligence, infliction of mental distress, breach of trust, fraud, breach of non-delegable duty and breach of fiduciary duty.”

The putative pastor who negotiated the 2009 out-of-court settlement with as many as 50 abuse survivors is now in jail because Canada Border Services found child pornography comprising 588 images, 60 videos and a 300-page porn novel on his computer. Bishop Raymond Lahey publicly espoused justice and reconciliation as he announced the settlement sitting beside abuse survivor Ron Martin Aug. 7, 2009. Two months later the bishop was under arrest. His passport is full of stamps from countries where sex with boys is openly sold in red-light districts.

There are no new lawsuits stemming from Lahey’s case. But seeing the first Catholic bishop anywhere in the world prosecuted for child pornography has shaken people’s loyalty to the Church. For Catholics and the community at large, the Catholic Church in Nova Scotia has been redefined by the sin of sexual abuse.

Nova Scotia was once a rural place with little churches nestled in little villages. It was full of priests, poverty and big families. Generations of often remarkable priests came off the farms and out of the coal mines. If they weren’t ordained close to home they joined religious orders and gave their lives of service to the Church in Canada and the world.

Rural life, to say nothing of Celtic tribalism, preserved old certainties and loyalties that were passed from generation to generation.

“We’re having to deal with a rural-based diocese confronted with all the difficulties of a secular world, with all the economic pressures, with the fact that a goodly number are moving out of those areas,” said Halifax Archbishop Anthony Mancini.

Small town Nova Scotia is disappearing fast. The fishery is long gone. Forestry employs more people maintaining equipment than cutting down trees. The steel mills are gone and the coal mines are closed. The Church has to adapt to a new reality. The people have moved to the city, where on Sunday the mall is open and Catholics are both shopping and working there.

“What we’re facing here is what Pope Benedict is calling a personal encounter with Jesus Christ. I believe that many of our people have never truly had that,” said Mancini. “They’ve been Catholic in form, but not necessarily Catholic at heart.”

“What we’re facing here is what Pope Benedict is calling a personal encounter with Jesus Christ. I believe that many of our people have never truly had that,” said Mancini. “They’ve been Catholic in form, but not necessarily Catholic at heart.”

Mancini wants people to discover exactly what Pope John Paul II meant when he coined the term “new evangelization.”

“He was talking to the Church in America. In the process, he said that is not a re-evangelization, and it’s not even a judgment on what was done before. What we’re looking for is a new evangelization in its ardour, a new evangelization in its method and a new evangelization in its expression,” he said.

Antigonish Bishop Brian Dunn agrees. Established in 1844, the Antigonish diocese includes parishes like Sacred Heart in the north end of Sydney, where attendance is 19 per cent of the church’s capacity and the tiny parish community is nearly $10,000 in debt. Out of 26 churches in the Sydney deanery, just three have attendance above 50 per cent of capacity. Three are under 20 per cent.

There’s a theoretical 126,000 Catholics in Antigonish served by 50 priests, who on average are 61.2 years old. Ten years from now, the diocese expects to be down to 30 priests. The diocese has one seminarian studying for priesthood and eight men discerning a vocation to the permanent diaconate.

The diocese had to put $7.8 million worth of church-owned real estate up for sale to pay for the Fr. Hugh Vincent MacDonald settlement. In dollar value, 20.6 per cent of it has sold. The church is also divesting itself of its 62 per cent share in The Casket, the local Antigonish weekly. Securities are being liquidated and more real estate sales are possible.

In a May 12 letter to parishioners, Dunn acknowledged that the diocese was facing difficult times due to decreasing population and the reality that church attendance and collections were both down.

“Furthermore,” he wrote, “the Legal Settlement has required that many surplus parish and diocesan resources have been depleted. As a result, some parishes are having (or will soon have) difficulty raising sufficient funds to maintain their church structures and to meet their other financial obligations,”

Parishioners are angry.

“People are saying we can’t afford these settlements,” said Angus MacIntyre of St. Theresa’s Parish in Sydney Mines. “(Parishioners) didn’t cause the problems but damn they’re going to pay for it though. We’re going to take your parish hall and we’re going to take your property and whatever is not essential and we’re going to get rid of it.”

The abuse settlement alone will not bankrupt Antigonish. But empty churches will. “We need to revitalize people who have left the Church or who have been on the edge of the Church,” Dunn said. “I don’t think we’ve lost a generation because of this (the sex abuse scandals). This has just exacerbated the situation.”

If Antigonish churches have empty pews, that started before sex abuse hit the headlines. There are economic and social causes that run deeper than the scandals. But the scandals have made the demographic and cultural reality more pressing and impossible to ignore.

Dunn goes to meeting after meeting where people ask who knew what when? And why didn’t we know? And why didn’t we act? They’re fair questions, even if he can’t answer. He’s committed to spending the rest of his life, if necessary, listening to people talk about their sense of betrayal.

“I’m not sure what we can do with the past,” he said.

Would it be better if there was a single, comforting answer or a simple explanation?

“We hear calls for transparency. We hear calls for accountability. We hear calls for being more responsible,” said Mancini. “All of that is a cry for something new. And behind all of that is a desire to be more credible and effective as disciples of Jesus Christ. But we haven’t figured out what being a disciple of Jesus Christ means at this moment in time.”

Sr. Donna Brady doesn’t believe in easy answers. Two months after Lahey’s arrest, Brady organized a group called Gathering the Wisdom in a Time of Crisis at the Sisters of St. Martha motherhouse in Antigonish.

“Myself, I was feeling the oppressiveness of silence and isolation. I said to myself, that’s what got us to where we are now — silence and isolation,” she said.

Originally there were just going to be a couple of meetings, but the 40 regulars didn’t want to stop. Brady doesn’t ask questions just of the bishops, chancellors and monsignors. She believes every Catholic has to answer for what their Church did and failed to do.

“This didn’t just happen. So what are the underlying factors? Why didn’t we see it coming? Where were we that we didn’t see this?” she said. “Going from being a victim to being a participant in Church (means) we have to be truthful as to where we were in this as well.”

In Yarmouth, the scale of the abuse settlements so far has been smaller. The diocese owes $2.6 million to the victims of Fr. Adolphe LeBlanc and Fr. Eddie Theriault. Of that, $1.5 million has been paid to six people who were between the ages of three and 15 at the time. The priests are now dead.

There are surplus properties up for sale in an unpromising real estate market. Interest from investments has been diverted into settlement payments, but so far the capital remains untouched. Diocesan Chancellor Sr. Marie-Paule Couturier hopes to preserve the churches, parish halls and cemetery funds. Everything else can be sacrificed.

But more trouble is coming down the pike. Fr. Albert Leblanc was charged in January with 40 offences involving boys seven to 11 years old. The alleged abuse occurred between 1970 and 1985 and Leblanc left the priesthood for a career in social work and then as a parole officer in 1973. The case of Fr. Raoul Deveau is also still working its way through the courts.

The priest, who died in 1982, is alleged to have sexually exploited Linda Deschamp over 10 years beginning in 1974, when she was 11 years old. The central battle in this case is whether Deveaux’s bishop transfered him to silence complaints about alleged misconduct involving another female child. The diocese has opened up its archives and no evidence has been found that indicates a cover-up, said Sr. Couturier.

Wherever the future settlements go, Yarmouth is getting smaller, older and poorer. The cotton mills are long gone. The ferry to Maine is gone. The tourism industry is in decline. Young people are getting out to find jobs where they can.

Between 2000 and 2005 median family earnings in Yarmouth fell 7.4 per cent. Half of Yarmouth families earned less than $32,901, compared to a national median income of $60,270 in 2005.

Yarmouth doesn’t need and can’t support 36 churches and chapels. The 13 parish priests don’t want to live in draughty, creaky old glebe houses.

One parish has already voluntarily decided it should merge with another rather than fight a losing battle to maintain its building. Couturier foresees future amalgamations will be decisions taken by the parishes themselves, not imposed by the bishop.

“Necessity will bring them there,” she said. “We can ride on illusion for a while.”

She remains optimistic about the future.

“People are saying, ‘Tell us facts. Keep us informed.’ I think that’s an expression of trust,” said Cutourier.

A shattered church seeks faith and hope

Nova Scotians recovering from crisis

|

|

|

“What we’re facing here is what Pope Benedict is calling a personal encounter with Jesus Christ. I believe that many of our people have never truly had that,” said Mancini. “They’ve been Catholic in form, but not necessarily Catholic at heart.”

“What we’re facing here is what Pope Benedict is calling a personal encounter with Jesus Christ. I believe that many of our people have never truly had that,” said Mancini. “They’ve been Catholic in form, but not necessarily Catholic at heart.”