Arts

Good news still flows with group’s live-stream

In the early 1980s, Canadian music icon Anne Murray released her classic country song, “A Little Good News,” in response to suffering she witnessed in society.

Our Lady of Guadalupe unveiled in new home

VANCOUVER -- When Vancouver art collector and philanthropist Michael Audain acquired a 300-year-old painting of Our Lady of Guadalupe, he knew the religious artwork needed to be displayed in an appropriate setting.

Ancient music given YouTube makeover

FRIBOURG, Switzerland -- Dominican Brothers Stefan Ansinger and Alexandre Frezzato are teaching people to sing 800-year-old Gregorian chant through free weekly lessons on their YouTube channel called OPChant.

The Resurrection revisited

Opera Atelier does not do anything by half-measures. This Easter, Toronto’s world-renowned company specializing in baroque opera is doing Handel’s The Resurrection full bore.

Grace before meals … and after and in between

The Catholic Register’s associate editor Michael Swan has taken one of his daily routines — praying — and turned it into a book, Written on My Heart. In it, he examines his experience with 10 memorized, traditional prayers and how they can deepen our relationship to the divine. In this excerpt from the book, he looks at how saying grace has played a role in his life.

I did not grow up saying grace at meals. At Christmas my father would jokingly recite some Latin grace he had learned while at university.

When I was an extremely bad Latin student in high school, I remember thinking not all of those sounds coming out of his mouth were words. I associated saying grace with a kind of lifeless, dour religion that serves as cover for a life filled with resentments and suspicion. It spoke to me of a sort of fearful narrowness and a brittle facade of outward propriety. If you are really grateful for food, you would eat it without hesitation and enjoy it. Solemnly pronouncing your gratitude is strictly a show — if not for others, then a desperate attempt to convince yourself.

Once you start down the road of grace before meals, where do you stop? Do you cross yourself before taking a sip of coffee at Tim Hortons? Do you recite a prayer before tearing open a bag of Doritos?

Food is integrally a part of our lives. To stand apart from your food while you pronounce upon it is to stand apart from life. Just as life is meant to be lived, food is meant to be eaten. Wouldn’t it make more sense after the meal? You don’t say thank you before you receive a birthday present. You open the present, react with surprise, delight, bemusement (pick one), then you say, “Thank you.” What if the meal is horrible? What if you get food poisoning? Are you going to thank God for that?

At various times, I have had to keep these thoughts to myself. I can remember one evening during the year I spent studying theology at Regis College, when the college choir finished off a rehearsal with an order of pizza. I hadn’t eaten all day. I was famished. The pizza appeared on a coffee table in the middle of the room with everyone standing around it in a circle. I stepped forward, opened the first box, tore a slice from its cheesy moorings then disappeared a third of it into my mouth.

One or two others swiftly followed my example. The Scottish Jesuit who played guitar for the choir was thunderstruck. He could not have been more shocked if an orgy had broken out in the theology students’ lounge.

“Aren’t we going to say any sort of grace?” he said in a panicked Scottish whine.

They all bowed their heads over their pizza while I guiltily chewed like a raccoon who had just dumped the best garbage in the neighbourhood.

The next year, when I joined the Jesuit novitiate, there could be no more displays like that one. I dutifully prayed before meals.

We novices were rotated through a schedule of daily prayer leaders. The prayer leader was to select morning prayers, serve at the daily Mass, lead evening prayers from the correct page in our breviaries and say grace before meals. We were strictly enjoined that this person was not to be called the prayer monkey.

Prayer monkey duties quickly became competitive. For morning prayer, world literature was scoured for deeper and higher and weirder petitions. Newspapers yielded more pathetic or outrageous tragedies to be prayed over. Background music was chosen, or we were led in song.

Art was displayed on an easel before the altar to focus our prayer. At meals, we went from brief preambles to “Bless us, O Lord,” to speeches that segued into “Bless us, O Lord,” to freestyle prayers that replaced “Bless us, O Lord.”

One day, one of the more sensible novices saddled with prayer monkey duties stood at his table before lunch, looked up, sighed and just blurted out, “Bless us, O Lord….”

When we finished the prayer, he said he knew a priest who, when asked to say grace before meals, would give the standard five-second “Bless us, O Lord” and then tell everyone he had a photocopy of the prayer if anyone wanted it.

In my second year at the novitiate, I was assigned to volunteer at an organization that helped Hmong refugees to either find jobs or qualify for welfare. I helped with teaching English to Hmong elders in their 60s and 70s who were never going to learn much English, but needed to go to the classes to qualify for continued welfare under President Bill Clinton’s welfare reforms.

At one point the job-search aspect of the program was looking for help. They had in the past been able to arrange tours of local factories and warehouses so that refugees would at least become familiar with the sorts of work they could expect. When these tours worked out well, the refugees were often invited to apply for jobs at the end of the tour. But the guy who had arranged these tours had moved on to some new career opportunity and the old regular tours were drying up.

I volunteered to cold call area businesses to see whether any of them would welcome a gaggle of middle-aged tribal hill people with limited English wandering across their factory floor to learn about work in America. I was pretty confident I could do this, because after coming home from New York with my lofty Master of Arts in Journalism from New York University, I had spent two years in various phone sales jobs.

I sold classified ads for The Globe and Mail, cable TV subscriptions for Rogers, home repair encyclopedias and romance novel subscriptions for a book marketing enterprise.

I also kept people on the phone for 20 or 30 minutes through their dinner hours answering survey questions about their consumption of unleaded gasoline and their feelings about immigration policy. I was a cold-calling telephone professional.

At that point, when I was a Jesuit novice volunteering with the Hmong-American Association in Minneapolis, I hadn’t done that sort of work in 10 years. Sitting down at the desk with a phone at my right hand and a list of business phone numbers to my left, I had a moment of doubt. I wasn’t sure I could deliver. I had told them what a great phone sales professional I was. Now I didn’t know what I was going to say to even get past the receptionist.

I can’t remember thinking about it at all. I simply gave into an urge, let out a deep sigh and started praying, “Bless us, O Lord….”

I was able that afternoon to sign up a couple of tours, including one at a place that made customized duotang binders for the school market. I later heard that while on the tour, several Hmong landed jobs.

I don’t think the prayer contributed all that much to the success of my two hours of cold calling. Nor would the prayer have been to blame if I had failed. But I remember a feeling of peace and acceptance come over me as I finished the prayer and picked up the phone.

I have since then thought it foolish to restrict this prayer to meals. I think, in fact, it is more appropriate in the face of the unknown, since we do not really know what gifts God will give.

It would certainly be very small of us to restrict our definition of God’s bounty to mashed potatoes and gravy.

So I wind up my morning prayer with this brief sentence of gratitude before I open the back gate and come back into our house to make breakfast and wake Yone, my beautiful wife.

Of course the prayer expresses gratitude for the cereal, toast and tea. But I know I have much more to be grateful for and I am constantly amazed at how well that one sentence reminds me that I am surrounded by gifts.

(Excerpted from Written on my Heart: Classic Prayers in the Modern World, by Michael Swan. Published by Novalis. To meet with Michael Swan, and purchase a signed copy of the book, come to the official book launch at the Mary Ward Centre, 70 St. Mary St., Tuesday, March 10 at 6 p.m. We can all say this prayer before enjoying the wine and cheese.)

Monk’s art challenges concept of ‘neighbour’

When Emmaus O’Herlihy prays the Magnificat every evening, he’s thinking about how young and powerless Mary was when she discovered she was pregnant and carrying the Saviour of the world.

Raphael's tapestries briefly return to Sistine Chapel

VATICAN CITY -- An artistic masterpiece conceived by the Renaissance master Raphael are on display for one week in the Sistine Chapel to help celebrate the 500th anniversary of the artist's death.

Author opens door to L’Arche’s world

Last year marked the 50th anniversary of L’Arche’s first community outside of France, L’Arche Daybreak, in Richmond Hill, Ont., and, sadly, it also saw the death of L’Arche’s visionary founder, Jean Vanier, in May.

For both of those reasons, L’Arche has been in the headlines to an unprecedented degree, and people around the world have been discovering both the movement and its founder, finding inspiration in its model of inclusive community life for people with intellectual disabilities.

To really grasp what life in L’Arche looks and feels like from the inside few could be a better guide than Beth Porter. Porter’s initial experience of L’Arche took place on the Labour Day weekend of 1980. She joined the community full-time in 1981 and has been an eyewitness to nearly 40 of the 50 years L’Arche Daybreak has existed. In this book — half-chronicle and half-love letter — she shares the growth and evolution she has seen in the community, and the transformations the community has evoked in herself.

Porter arrived at L’Arche as a young university graduate and teacher, searching for spiritual meaning and eager for community. She had explored great religious and mystical thinkers through her undergraduate years. She had gone to Trinidad to teach with Canadian University Service Overseas (CUSO) and had returned knowing that she wanted to make a difference in the world. Her journey led her first to the Anglican Church and then to Catholicism and repeated encounters with Jean Vanier’s writings about community.

She decided to see whether L’Arche might be a good fit for her and vice-versa. Her answer came in the form of a 38-year journey of discovery. She leads readers through the friendships and daily activities, the frequent joys and occasional frustrations, that are the threads of a remarkable tapestry that today includes 31 Canadian communities and more than 150 around the world.

Porter introduces us to dozens of people who have been part of the L’Arche communities she has lived in, whether they are core members (men and women with some degree of intellectual disability), assistants (those who live with them, offering support and friendship), volunteers, leaders and friends of the community. She has remarkably detailed memories, which allows her to sketch out personalities, events and conversations — capturing both the way things unfolded and her own impressions and reactions. She speaks lovingly and candidly about members of the community, their gifts and contributions and, occasionally, their shortcomings and quirks. She recalls moments of shared joy and laughter and recounts times of pain and awkwardness.

She gives us access to a double inner life — the life of L’Arche (especially at Daybreak) and her own inner life as she is stretched by people and events over four decades. Her stories inspire laughter and admiration, but she doesn’t hesitate to admit the rough edges that are also part of living in community. She includes her own mistakes, conflicts and misunderstandings, moments of doubt and questioning — so much so that the reader sometimes has the uncomfortable sense of reading someone else’s diary with all its intimate and deeply personal revelations.

There is an obviously tender love for L’Arche and the people who have accompanied her on that journey.

As Porter repeatedly highlights, Vanier’s vision was of people doing things with and not for others. It is a life of normality, where each person makes their own contribution, both giving and receiving.

These stories are touching and evocative, and they make up the substance of this book. There are two other elements, however, that I think highlight key aspects of L’Arche Daybreak. First is Porter’s inclusion of a chapter about the late Henri Nouwen. During his life and perhaps even more since his death in the fall of 1996, Nouwen has been recognized as one of the great spiritual writers of the past 50 years.

Porter knew Nouwen personally, as L’Arche’s pastor, as a community member and as an intellectual she could engage with on the level of spirituality and ideas. She presents Nouwen three-dimensionally and honestly, highlighting how he helped to shape today’s Daybreak and how L’Arche shaped him as a human being and priest.

Related to this is a second element — L’Arche’s ability to be both a Catholic community and an open, ecumenical and interfaith one. Vanier came from a profoundly Catholic upbringing, which left its imprint on his worldview and spiritual outlook. But, as Porter repeatedly underscores, L’Arche has never been denominational or chauvinistic.

Its worship moves comfortably between Catholicism, Anglicanism, the United Church and the ecumenical Taizé community. Porter herself has been actively involved in Christian-Jewish dialogue and has studied Judaism extensively. Daybreak’s chapel décor includes a painting of a mosque, with the first verse of the Qur’an written in Arabic.

L’Arche’s radical welcome and inclusivity extends to the spiritual realm, where people seek to respect each other and learn wisdom from them. In that sense, L’Arche is a parable of what is possible and needed in our fractious, competitive world.

Accidental Friends is an ideal title for this book. Many of its characters came into Porter’s life unexpectedly and unintended, yet her book makes clear how those friendships were providential and life-changing. This book is a tribute to how openness to friendship can transform us.

It is an invitation to discover our full humanity. It is filled with gentle, spiritual wisdom and a cast of characters who remind us why L’Arche is such a special gift to the Church and why L’Arche Daybreak is such a precious gift to us here in Canada.

(Watson is a Catholic Scripture scholar and interfaith educator. He is the Adult Faith Formation Animator for the Simcoe Muskoka Catholic District School Board and has been a friend of the L’Arche movement for many years.)

Accidental Friends: Stories From My Life in Community

by Beth Porter

Novalis, softcover, 275 pages

$22.95

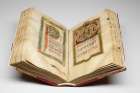

Baltimore museum showcases medieval missal used by St. Francis of Assisi

BALTIMORE -- More than eight centuries ago, St. Francis of Assisi and two companions randomly opened a prayer book three times inside their parish church of St. Nicolo in Italy.

Sport and faith: It’s more than a game

When it comes to books about sports, there’s plenty of “fun reads” out there, but Matt Hoven saw there was something missing for those who take the study of sport seriously.

Faith, humour go to work on tumour

WASHINGTON -- Jeannie Gaffigan didn’t initially set out to write a book about having her brain tumour removed.

Homeschooling mom fills in gap on martyrs

VANCOUVER -- Vancouver mom Bonnie Way has long been inspired by the Canadian martyrs, eight Jesuit missionaries who in the 1600s gave their lives to preach the Gospel to North America’s Indigenous peoples.

Author’s pillars could use extra support

With gratitude, generosity and mindfulness as his three foundational pillars, Fr. Darrin Gurr wants to examine a spirituality of stewardship. The result is a helpful guide to those who want to find meaning in acts of generosity, but the book lacks originality and some of its themes remain undeveloped.