Back on the ground, other Jesuits told me that Maurice’s wild enthusiasm for whatever was before him, combined with a complete lack of self-regard, was not unusual. For years Maurice had hitched rides on the CNR train through Northwestern Ontario, picking up donations of building materials so he could build and repair mission churches along the north shore of Lake Superior.

He was a missionary first. He had slept in the vestries of those wooden churches, keeping warm by the furnace-cum-stoves he made from old oil drums. He built those churches and slept in them so he could celebrate Mass for the people, baptize their children, marry them, bury them and share their lives.

Maurice was also a hockey coach who had guided the Wikwemikong Thunderbirds of the tough Northern Ontario Senior League. In fact, he played his last hockey game at 70 and went for a skate on his 90th birthday. When he was young, he taught math at the Garnier Residential School in Spanish, Ont., and at Campion College in Regina. He had been a pastor of St. Anne’s parish in Fort William (and its 12 missions) and of St. Theresa’s in Beardmore.

He knew Northwestern Ontario and its native people so well he ended up working for both the federal and provincial governments. Maurice had stints as a prison chaplain, a military chaplain and had served his Jesuit brothers as superior of the communities in Wikwemikong and in Thunder Bay.

The last 20 years of his life — his so-called retirement — were spent as a genealogist and historian. He sat down with all the dusty registers of baptisms and marriages from all the Jesuit missions in Northwestern Ontario, going as far back as 1850. He created indexes of names with their multiple spellings. From there he was able to trace family histories of native people all over the north shore of Lake Superior.

Despite this long list of accomplishments, Maurice was never one of those famous Jesuits. He died in the spring of 2008 beloved by many. He was never an important professor, president of a university or celebrated author. In the 400-year history of the Jesuits in Canada, he was just another Jesuit — one more who gave his life completely, without reservation, to the mission.

What Maurice did is what Jesuits have been doing since Pierre Biard and Ennemond Massé sailed into Port Royal on May 22, 1611. They were the first Jesuits to arrive in what we now call Canada. Four hundred years ago it was called New France and the early Jesuits, in the missionary spirit of their founder Ignatius Loyola, arrived to bring the Gospel to the indigenous peoples.

But facing English marauders from Virginia and a lack of support from the French administration

in Port Royal, Biard and Massé returned to France after just a couple of years. The Jesuits, including St. Jean de Brebeuf, didn’t return until 1625 — this time based in Quebec City. They established Canada’s first parish in 1634, Canada first college (which became Laval University) in 1635 and by 1639 they’d led Huron Chief Joseph Chihwatenha in praying the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola.

Brebeuf was of the Jesuit tradition that couldn’t wait to venture out to the very edge of the known world — whether physically or intellectually. The Jesuit mission in Canada was a vast scientific inquiry into the nature of the new world. The Jesuits who came were more than evangelists. They were linguists, astronomers, chroniclers, cartographers and ethnologists whose work shaped Canada’s early history. Eight of them were martyred for their faith. (The tale of their sacrifice is elsewhere in this section.)

When in 1672 Fr. Jacques Marquette and former philosophy student Louis Joliet journeyed from Quebec City to map the Mississippi and record their observations of the people who lived between the Great Lakes and the Arkansas River it was an enormous expansion of European knowledge about North America. Likewise

Education, pastoral and spiritual guidance, missionary work among native people and a dedication to justice — that’s what the first Canadian Jesuits did in the 17th century. It’s what Maurice did in the 20th century. It’s what Jesuits continue to do.

From the beginning, Jesuits were men on fire. They were willing to suffer any hardship, undertake impossible tasks, do whatever it takes to share their love of Christ. Each and every Jesuit arrives at that point through the Spiritual Exercises of St. Ignatius of Loyola — 30 days of silent contemplation and meditation on the life of Jesus.

European politics played havoc with the Jesuits’ Canadian saga. In 1759 the Seven Years’ War between the British and the French brought a British victory on the Plains of Abraham. New France was gone and the British held an enormous colonial empire in North America. The English regime, long separated from Rome, wasn’t about to allow French Jesuit priests to continue arriving in North America. But they did allow the Jesuits already in Canada to continue ministering to French-speaking Catholics.

At the same time, European nobility — especially those who were getting rich off slave-run plantations in the New World — were determined to stop Jesuits from interfering in a profitable enterprise. In 1773 Pope Clement XIV gave in to pressure from the French Bourbon court and suppressed the Jesuit order. But the British administration in North America had no interest in promulgating the Pope’s decision. Canada’s Jesuits were allowed to carry on while their brothers in Europe lost their ministry. But, the supply of new Jesuits dried up and the British confiscated Jesuit lands. The last Jesuit in Canada from before the English conquest was Fr. Jean-Joseph Casot. He died at Quebec in 1800.

Though Pope Pius VII re-established the Jesuits in 1814, it wasn’t until 1842 that the restored Society returned to Canada. But there was no return of their confiscated properties. Catholic bishops in Quebec had begun to petition for the return of Jesuit lands as far back as 1838. After Confederation in 1867, when the Jesuit estates passed into the hands of the government of Quebec, the bishops urged some sort of negotiated settlement.

The issue stirred up Protestant sentiment, with the Orange Order campaigning against papist influence in Canadian affairs. But in 1888 the Jesuits’ Estates Act passed, giving the Jesuits $160,000 to surrender their claims to property, plus $140,000 for Université Laval, $100,000 to a number of Quebec dioceses and, in a political compromise, $60,000 to support Protestant higher education in Lower Canada.

Just as the 17th-century French Jesuits sent missionaries to Canada, the 20th century Canadian Jesuits went out to distant lands. Beginning with three Quebec Jesuits going to China in 1918, Canadian Jesuits have sent missionaries to at least 15 other countries, including some of the most unlikely and difficult mission lands imaginable — Bhutan, Nepal, Tanzania, China. Some of those missionaries, like Brebeuf and his companions, became martyrs.

Three French Canadian Jesuits, Frs. Prosper Bernard, Alphonse Dubé and Armand Lalonde, were executed in China in 1943. Japanese occupation forces killed them for running a safe zone that saved thousands fleeing the war between Chinese nationalist forces and the Japanese in Anhui Province.

In 2001, Fr. Martin Royackers was shot dead standing in front of his church in Annotto Bay, Jamaica. He had been preaching against the bully tactics and corrupt politics of certain Jamaican landowners who tried to block small farmers from claiming land they legally owned.

Royackers, Dubé, Bernard and Lalonde have a lot in common with their 17th-century predecessors. They stood on the side of the poor and the weak praying for reconciliation, sanity, even just a little humanity.

In the 1640s, agrarian Hurons were easy prey for the Iroquois, whom the Dutch had armed with the latest weapons. When Fr. Paul Ragueneau and his fellow Jesuits decided in 1649 to burn down their own mission at Ste. Marie near Lake Huron, it was so they could travel with the Hurons to establish a safe haven on Christian Island in Georgian Bay. The French Canadian Jesuits in eastern China also created a safe haven during the Second World War, protecting poor peasants from a war visited on them from outside. Royackers worked to establish an economic safe haven for the poor farmers of Annotto Bay — a zone where they could make a living in spite of globalized free trade and plundering by Jamaica’s own land-owning class.

Jesuits didn’t start talking about who they are and what they do in terms of “faith that does justice” until the 1970s, but those words weren’t an invention or an innovation after the Second Vatican Council, they were true for Brebeuf and Lalemant, true for the more recent martyrs, and true for forgotten Jesuits who taught school and delivered the sacraments across Canada for four centuries.

In 1613, 29-year-old French sailor and merchant Jean Dirou became the first person in Canada to join the Jesuits. Biard sent him back to France so he could go through the novitiate and become a brother. Though the brothers are often thought of as mere enablers of the priests — simple, pious men who keep the boilers working in Jesuit colleges — Dirou set quite a different course. He was captured by Muslim pirates, then sold as a slave to a merchant. The merchant promised to make Dirou his heir if he married his daughter. Dirou escaped, was picked up by a Christian ship, re-entered the novitiate in 1617 and took vows in 1619.

Jesuit Brother Nick Johansma had nearly as adventurous a life. In 1971 the Dutch-born Johansma was invited into Bhutan by the kingdom’s Queen Mother. He set up an agricultural college that helped modernize farming in Bhutan. He was so good at it he ended up running agricultural programs in Jamaica, Zambia, India, Liberia and Ethiopia. In the 1990s the expert in agriculture lived in downtown Toronto working with refugees and the homeless.

The suppression of the Jesuits in 1773 stunted Jesuit growth in Canada for a couple of generations. But once they were back under the visionary leadership of Fr. Felix Martin — who helped organize relief for the thousands of desperate Irish refugees flooding into Montreal and designed and built the College Sainte-Marie which eventually became the centrepiece of the Université du Quebec a Montréal — they went straight back to work. The Jesuits started training men in Canada with the first novitiate in Montreal in 1843.

In 1845 the Jesuits took over the mission on the unceeded Native reserve on Manitoulin Island, which is Canada’s oldest continuous mission. By 1847 the Jesuits were recognized as such an important force throughout Canada that one of the first English Canadian Jesuits, Fr. John Larkin, was nominated to replace Bishop Michael Power, the first bishop of Toronto who died ministering to typhus victims among the thousands of Irish refugees who landed in Toronto that summer.

Larkin returned the papal bull communicating his appointment unopened and departed to study theology in France before another could be delivered. Though his Jesuit friends and others urged him to accept the post of bishop, Larkin insisted his vocation was to religious life with the Jesuits. Eventually Pope Pius IX was persuaded to appoint Bishop Armand de Charbonnel in 1850.

English Canada got its own novitiate in Guelph in 1913. The brothers grew the food on the farm in Guelph, where life wasn’t always easy. There are older Jesuits alive today who remember the instruction that if they didn’t hear the lunch bell, don’t bother coming. Silence would mean they had run short of food.

Despite very real poverty, the Jesuits bulled ahead and established institutions in English Canada for every stage of Jesuit formation, including a juniorate in Guelph which began in 1915 for two years of study in Latin and Greek. The three years of philosophy studies were conducted at College de l’Immaculeé-Conception in Montreal beginning in 1885, with English Canada getting its own philosophate in 1930. Theology studies at Regis College in Toronto began in 1943. Regis became a pontifical faculty with the ability to grant ecclesiastical degrees in 1956 and eventually moved to the campus of the University of Toronto in 1976.

Growth in English Canada took off when the Canadian province was split into English and French in 1924.

The Canadian Jesuit intellectual tradition goes beyond the colleges they’ve built. Fr. David Stanley was one of a generation of scholars who embraced modern biblical scholarship after Pope Pius XII issued Divino Afflante Spiritu in 1943. More importantly, he made scripture intelligible to ordinary people. Bishop Attila Mikloshazy is author of a five-volume history of the liturgy. Most impressive of all was the contribution of Fr. Bernard Lonergan, author of Insight: A Study of Human Understanding, Method in Theology and For a New Political Economy.

This Canadian Jesuit intellectual tradition can be traced back to Brebeuf, whose writing about native people and their languages became a treasure trove for future generations of ethnologists.

“Publish or perish,” has long been a snide, snickering little joke about the intellectual pride of Jesuits, as if the real object of a Jesuit vocation was a comfortable academic sinecure; as if those who didn’t become professors were optioned to the farm team, preaching Sunday sermons. But Jesuits were the only priests in Canada from 1632 to 1658, and pastoral ministry (running parishes and giving retreats) has always been their core business.

There are Jesuit parishes in St. John’s, Newfoundland (St. Pius X), Toronto (Our Lady of Lourdes), Guelph (Holy Rosary), Sudbury (Ste-Anne-des-Pins), Thunder Bay (St. Anne), Winnipeg (St. Ignatius), Vancouver (St. Ignatius of Antioch and Holy Name of Jesus) and a Jesuit chapel in Montreal.

Jesuits don’t pastor aimlessly. They pastor their flocks toward and through the Spiritual Exercises of their founder, St. Ignatius of Loyola. That means pointing people toward a closer relationship with Jesus. In the Spiritual Exercises people use their imaginations to enter into the life of Jesus, picturing themselves present in the stories of the Gospels.

To offer people this opportunity, Jesuits have built retreat houses. Ignatian spiritual centres giving one-day to 40-day retreats include the Ignatius Jesuit Centre in Guelph, Manresa in Pickering, Anishnabe Spiritual Centre in Espanola, the Jesuit Centre of Spirituality in Halifax, the Ignatian Centre in Montreal, Centre de Spiritualité Manrèse in Quebec City, the St. Ignatius Adult Education Centre in Winnipeg and the Jesuit Spiritual Exercises Ministry in Vancouver.

Canadians played a huge role in the modern renewal of individually directed Ignatian reteats. Through the 19th and into the 20th centuries the practice of meeting individually with retreat goers, asking about their prayer and leading them through meditations had fallen away, even though it had been the practice of St. Ignatius and his followers. By the 1970s Fr. John English, having spent years as a novice master in Guelph, was ready to revive the practice following in the footsteps of fellow Canadians Fr. David Asselin and Fr. Gilles Cusson. English wrote Spiritual Freedom: From an Experience of the Spiritual Exercises to the Art of Spiritual Direction, a book used to train spiritual directors around the world. It is part of English’s legacy that the world comes to Guelph to learn to give the Spiritual Exercises.

This revival of Ignatian spirituality as a gift to the whole Church dovetailed perfectly with another transformation of Jesuit tradition. Beginning in 1967, the Jesuit-founded Sodalities of Our Lady took on new life as the world-wide Christian Life Community. CLC is a network of small groups who live the Spiritual Exercises every day, encouraging each other in prayer and action.

Canadian Jesuits have invited lay people, religious and secular priests to walk with Christ through Galilee, stand with Him in the Temple of Jerusalem. Following the Spiritual Exercises means watching Christ betrayed, arrested, flogged, condemned and crucified to satisfy the narrow interests of people who have power. It’s an experience that produces people with a certain edge. That gets Jesuits into trouble, sometimes.

In 1997 the Jesuit Centre for Social Faith and Justice produced a poster featuring the faces and names of Canada’s top earning CEOs. It was called “Exposing the Face of Corporate Rule” and sold out very quickly. It was also condemned by conservative politicians and journalists and banned from Toronto parishes by auxiliary Bishop John Knight.

It ruffled feathers. It made people uncomfortable. Every word on the poster and the campaign behind it was meticulously researched and documented. It was very Jesuit.

When Fr. Jim Profit, founder of the Ecology Project in Guelph, tells us the Earth can’t sustain globalized industrial farming or the level of consumption we take as normal in North America, he doesn’t expect everyone will agree of the Jesuit Refugee and Migrant Service defends the rights of refugees, he’s not surprised that people counter with tales of dubious refugee claims. When Fr. Bill Ryan lays out just how a society deeply divided between rich and poor runs counter to the Gospel and against the reconciling, unifying prayer of Jesus he doesn’t expect a round of applause.

The Jesuits aren’t on the side of popular opinion. They’ve never settled for the comfortable position. They don’t care if they rock the boat.

That sort of independence of mind was always the hallmark of a Jesuit education. Rene Levesque, Pierre Trudeau, Jean Vanier, Robert Munsch and plenty of other interesting, independent thinkers have graduated from Jesuit high schools and colleges.

In 1940 there were seven French and five English high schools, plus two bilingual colleges in Canada. As provincial governments have phased out denominational schools in parts of the country, the Jesuits find themselves concentrating their efforts on fewer schools today. They helped set up and continue to support St. Bonaventure’s College high school in St. John’s, Nfld. Campion College at the University of Regina, Sask., is theirs, as is St. Paul’s High School in Winnipeg. There’s Loyola High School and College Jean-de-Brebeuf in Montreal. At the University of Toronto, you can earn your PhD, licentiate or a masters degree in theology at Regis College.

But schools are merely the obvious. Jesuit education in Canada today also means the Jesuit Communication Project, which has been teaching teachers how to incorporate media literacy in the classroom for more than 20 years. For 13 years the project’s founder, Fr. John Pungente, has been bringing that education directly to television audience with his shows Scanning the Movies and Beyond the Screen.

Camp Ekon gives kids an experience of nature, community and Christian leadership skills on the shores of Lake Joseph in Muskoka.

Jesuits provide campus ministry to university students at the University of British Columbia and also help out the chaplaincies of the University of Guelph and at the Newman Centre at the University of Toronto.

Mens sana in corpore sano was always a motto of Jesuit education. A sound mind in a sound body is a fine goal for any young person. But for Jesuits that was only ever a beginning. They want those minds and bodies dedicated to something greater than themselves. For the Jesuits that something is someone, and His name is Jesus. Today, the motto for Jesuit education is “men and women for others.”

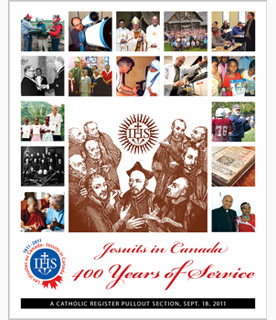

In the centre of the Jesuit seal are the letters “IHS,” a Greek monogram of Jesus’ name. Around that monogram is the sun. Beneath the sun is a heart representing the love of Christ and three nails that stand for poverty, chastity and obedience. It all adds up to one yearning, one hope, one ideal – Ad maiorem dei gloriam.

Jesuits 1611-2011: 400 years of giving

By Michael Swan, The Catholic RegisterI met Jesuit Father Bill Maurice on the roof of the mission house on the Fort William Reserve, on the edge of Thunder Bay, Ont. He was repairing an outdoor loudspeaker which he had mounted to broadcast prayers and other vital messages to the surrounding households.

It was early spring with the wind whipping off Lake Superior and I had been wondering why an 82-year-old man was scrambling about on the roof with a pair of pliers and a screwdriver. Once he had persuaded me up to the roof and started handing me tools I was not so much mystified as aghast. As he handed me tools, he was talking.

Maurice had opinions about theology, liturgy, politics, the weather, hockey and everything else but I wasn’t catching much of it while I hung on to the TV antenna. I eventually learned Maurice wasn’t just a colourful, crazy character. He was a Jesuit, one of more than 2,000 Jesuits who have been entwined in Canada’s history since 1611. Just as students in Jesuit schools inscribe the top of their exam papers with AMDG, the old priest had carved Ad Maiorem Dei Gloriam (“to the greater glory of God”) into his soul and into every day of the 92 years he lived.

Please support The Catholic Register

Unlike many media companies, The Catholic Register has never charged readers for access to the news and information on our website. We want to keep our award-winning journalism as widely available as possible. But we need your help.

For more than 125 years, The Register has been a trusted source of faith-based journalism. By making even a small donation you help ensure our future as an important voice in the Catholic Church. If you support the mission of Catholic journalism, please donate today. Thank you.

DONATE