Michael Swan, The Catholic Register

Michael is Associate Editor of The Catholic Register.

He is an award-winning writer and photographer and holds a Master of Arts degree from New York University.

Follow him on Twitter @MmmSwan, or click here to email him.

Family caught in Lebanese limbo

The Army of the Murabi Islamic Iraq State doesn’t like what Fuad Benan Kakos did for a living, and if they ever catch him they’re going to kill him. They gave him and his family a three-day head start. Fuad, Jacqueline and their sons David and Eliot have been in Beirut just over a year.

The Army of the Murabi Islamic Iraq State doesn’t like what Fuad Benan Kakos did for a living, and if they ever catch him they’re going to kill him. They gave him and his family a three-day head start. Fuad, Jacqueline and their sons David and Eliot have been in Beirut just over a year.The family had lived in the Christian neighbourhood of Zafaraniyya in Baghdad. Fuad made a modest living running a shop that had a dangerous sideline: under-the-counter liquor sales — legal for Christians under Iraqi law, but dangerous if the mujahedeen find out.

Dream is not shattered

Menirva is hanging onto her dreams. She’s 18. She’s lived as a refugee and a sweatshop seamstress since she was 14. Dreams are all she has.

Menirva is hanging onto her dreams. She’s 18. She’s lived as a refugee and a sweatshop seamstress since she was 14. Dreams are all she has.“I don’t want to drop my dream. I always want to keep our hope alive, that someone will help us, will accept us. I cannot imagine that I will accept life here,” she said, and the tears begin. “I am tired. I cannot take it any more. I want to continue to dream.”

For Christian refugees, 'There is no future in Iraq'

The death threat was no surprise to Ihab Ephraim Khodr. He had seen it happen to other Christians. There had been plenty of other vague and general threats, year after year, before he received a personal threat just before Iraq’s March 7 elections. He had been waiting for it.

The death threat was no surprise to Ihab Ephraim Khodr. He had seen it happen to other Christians. There had been plenty of other vague and general threats, year after year, before he received a personal threat just before Iraq’s March 7 elections. He had been waiting for it.His expectation is inked into his right wrist.

In his student days in the first half of the decade, Ihab had begun to get a tattoo that would have portrayed a crown of thorns wrapped around his wrist. It was to be a sign of his devotion to Christ. It also would have made him recognizable on the street as a Christian.

Past the point of no return

An election victory for Iraq’s more secular, less sectarian parties backing Prime Minister-elect Ayad Allawi isn’t tempting Iraqi Christian refugees to return home, even as members of the Chaldean Church hierarchy continue to express confidence that Christians can live in peace in Iraq.

An election victory for Iraq’s more secular, less sectarian parties backing Prime Minister-elect Ayad Allawi isn’t tempting Iraqi Christian refugees to return home, even as members of the Chaldean Church hierarchy continue to express confidence that Christians can live in peace in Iraq.“It’s very, very difficult to turn back to Iraq, impossible to turn back,” Toma Georgees told The Catholic Register in his apartment in the Geremana neighbourhood of Damascus, Syria. “Our problem is not with the Iraqi government. Our problem is with Iraqi people, ignorant people who want to kill us, who want to kill all the Christians... Those people are ignorant, and they just want to drink our blood as Christians.”

ANALYSIS : Christians are essential to Middle East's future

You don’t need to know a word of old Syriac or Aramaean, not a word of Arabic. You don’t need to know the stories of kidnappings, death threats or the desperate flight to the border. You don’t need to know how these people have lived for years in exile on borrowed money, tea, sugar and bread.

You don’t need to know a word of old Syriac or Aramaean, not a word of Arabic. You don’t need to know the stories of kidnappings, death threats or the desperate flight to the border. You don’t need to know how these people have lived for years in exile on borrowed money, tea, sugar and bread.

From the moment you walk into a church filled with Iraqi refugees in Syria or Lebanon their faith, their devotion, their steadfast love of God is as real, as concrete, visible and tangible as the walls of the church.

Exodus Iraq: A flight to safety, a cry for help

Beirut / Damascus - In 2006 there was an explosion at the church where Zuhaila Mikha’s husband used to help out. Ramzi was killed. Then in July, 2007 Mikha’s 19-year-old daughter was kidnapped. After two months of asking police and hospitals for information about her daughter she got word from her neighbour: “Let your neighbour know she should not go to the police or we will kill her.”

Beirut / Damascus - In 2006 there was an explosion at the church where Zuhaila Mikha’s husband used to help out. Ramzi was killed. Then in July, 2007 Mikha’s 19-year-old daughter was kidnapped. After two months of asking police and hospitals for information about her daughter she got word from her neighbour: “Let your neighbour know she should not go to the police or we will kill her.”

She moved from Mosul to the nearby Christian village of Tel Eskoff. But after nine months trapped in the village — running out of money, afraid to go to the city, afraid to let her children out of her sight — it was time to get out of Iraq.

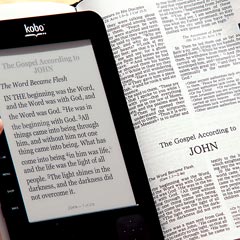

The Bible goes high-tech

Everyone who reads has at some time or other been psychologically kidnapped by a book. A great book carries us away. They are populated with friends, allies, enemies, protectors and persecutors. Great books teach us how to fall in love, answer when challenged, hope when hopes are dashed, cry when we are hurt and laugh for the sake of laughter.

Everyone who reads has at some time or other been psychologically kidnapped by a book. A great book carries us away. They are populated with friends, allies, enemies, protectors and persecutors. Great books teach us how to fall in love, answer when challenged, hope when hopes are dashed, cry when we are hurt and laugh for the sake of laughter.Few of us would honestly name the Bible as a psychological surround sound experience. For most, it’s hard to immerse ourselves in the world of the Bible.

I recently began a new journey into the Bible’s gated and guarded world when I received a Kobo Reader for Christmas.

A Kobo Reader is a simple electronic device that connects to the Internet and lets you download books that can be read on a small screen. There are thousands of books to choose from and I started with the oldest of them all, the Bible.

For many good reasons, the Bible isn’t a book that sweeps us away. First, it isn’t a book. It’s a collection of books assembled 1,700 years ago from literature that dates as far back as 1,200 B.C. The books of the Bible were written in either Hebrew or Greek, and some were written about people who spoke other, equally distant languages, including Aramaic, the language of Jesus.

Basketball molds St. Joe’s team into one big family

TORONTO - Most basketball players have a conventional notion of what makes a great basketball photo. The great photos show a player rising above the rest — a hand blocking a shot, a rebound plucked out of mid-air, a shot launched with precision.

TORONTO - Most basketball players have a conventional notion of what makes a great basketball photo. The great photos show a player rising above the rest — a hand blocking a shot, a rebound plucked out of mid-air, a shot launched with precision.But those heroic moments aren’t how 5’9” centre Cesarine Moundele of the St. Joseph’s College School Rough Riders thinks of her sport or her team. When I asked the team what sort of picture would best tell the story of basketball at their school, Moundele said, “A picture of the bench.”

Teammates all around her agreed. What makes their team is all of them, together, cheering each other, supporting each other.

“We’re like family,” said 5’0” guard Christi-Ann Miole.

The Rough Rider’s improbable coach Francesco Maltifitano — who made his mark playing soccer, not basketball — turned away from the kids to hide his smile. He was as proud of this answer as he was of any of their wins.

Challenged to say why basketball should matter at all in a Catholic school, 5’4” guard Raize Dela Pena said, “You learn teamwork. You know you’re not alone in the world.”

In the tent camps around Port-au-Prince, in the collapsed and desperate slums of Cite Soleil, amid the violence of a chaotic city policed by United Nations troops from around the world there’s a pro-life story.

Kay Famn (Creole for the House of Women) doesn’t call itself a pro-life organization. The Development and Peace partner proudly claims the title feminist. What Kay Famn does, however, lifts up women and the value of life in the face of violence and the most corrosive poverty in the Western Hemisphere.

Before the earthquake Kay Famn ran one of the only women’s shelters in Haiti — a country where until 2005 rape was considered a crime against honour rather than a crime against a person. Now with more than one million people crammed into tent camps where there are no locked doors and the shadows at night hide all kinds of crime, Kay Famn is seeing a steady stream of girls, many between 13 and 15, come to them pregnant.

“They arrive pregnant and give birth here,” Kay Famn co-ordinator Yolette Jeanty told The Catholic Register.

Somebody has to prepare the girls for motherhood.

“They’re kids we are preparing to give birth,” said Jeanty. “They don’t have families. They stay with other kids.”

The program is called Revive. In addition to dealing with the trauma of the girls’ situation — whether they’ve been raped, seduced by an older man or surprised to discover they are pregnant — Kay Famn tries to keep the girls in school or at least provide basic literacy and job training.

If not for Kay Famn, no end of illegal and dangerous abortions are performed in Haiti. Given the state of health care, the girls chances of surviving child birth without Kay Famn are low. Even before the earthquake, the maternal mortality ratio for Haiti was 670 for every 100,000 live births, according to Unicef.

The problem is bigger than Kay Famn can deal with. They’ve got room for about a dozen girls at a time. They can offer financial support for 40 girls. Out there in the camps there’s an epidemic of sexual violence and a kind of brutal economy in which sex is traded for protection, food and shelter.

All of that means there’s good reason to help Kay Famn with financing and strategy, said Development and Peace executive director Michael Casey.

“You look at that tragedy, that kind of thing happening to very young girls, the violence being perpetrated against women in the camps — the stuff that Kay Famn is working with,” he said.

“Those are very, very important stories.”

“There’s a lot of sexual violence against little girls and adolescents,” said Jeanty. “Men are using violence to bring girls to bed. Or trading rice for sex.”

Kay Famn does not advocate for abortion access because that won’t solve Haiti’s problem with sexual violence and predation. They do what they can for the girls who come to them.

“The situation in the camps has exacerbated the problem,” said Jeanty.

- RAISING UP HAITI -

a Catholic Register special report

Haiti's churches need healing [slideshow]

What now in Haiti?

Post-traumatic stress proves difficult

Catholic aid organizations fly under the radar

Canadian engineer to oversee Haiti’s Church rebuild

Haiti must take this opportunity to change

Crisis makes D&P rethink how it operates

Bold education plan held up by a lack of funds

Church holds community together

D&P-funded program provides pro-life solution to Haiti's sexual violence

Haitians must look to themselves to rebuild their nation

Church holds community together

Madame Odessi Petit Foin knows exactly what she’s missing since the church in Duvale collapsed, along with her house and most of the other houses in the farming community.

Duvale always did need lots of things. It was never rich. It needed a new road before the earthquake and now it needs it more. It has needed a new school for a long time and thanks to the earthquake it got one — built with aid money on the foundations of the collapsed church. And it needs houses for the families still living in tents by their tiny plots of tomatoes, cucumbers and peas.

In Petit Foin’s opinion, Duvale also needs its church.

“It preaches morality and conversion,” she said.

She also makes the point that it’s through the church that Duvale gets access to the international aid money which will finance a new Caritas Port-au-Prince agricultural improvement project. But that’s not the most important reason that Duvale needs its church.

“The church in Duvale plays a very big role that holds together friends and family,” she said.

Petit Foin is not an economist, a politician, a theologian or philosopher. But as she stands in the old church hall, which has become the church in Duvale, she’s hit upon something quite important.

There’s more to infrastructure than the efficient delivery of goods to market on safe, smooth and broad roads. A community requires infrastructure so it can hold together, so it can know itself and meet the world. Duvale needs its church so that it can be a community which people recognize when they see the church.

The people of Duvale themselves need to recognize that they are a community of families when they meet for Sunday morning Mass.

There is such a thing as spiritual infrastructure. In fact, if Duvale had a great road connecting it with Port-au-Prince but its people had lost their way and no longer knew themselves, no longer cared for each other, no longer lived in and for their families — well, that would be a road to nowhere.