Which was all rather surprising as Tebow is hardly alone in demonstrations of religious faith on the field. Indeed, in his last victory of the season, Tebow was not even the most overtly religious player on the field. That distinction belonged to Pittsburgh Steelers’ Troy Polamalu, who crosses himself after every play. Perhaps because Polamalu is an Orthodox Christian it gets less noticed, as the Orthodox are a small minority in America compared to evangelical Christians, which Tebow is.

Incidentally, in relation to Orthodox Christians crossing themselves during play, have there ever been more intense Signs of the Cross than those made by tennis player Novak Djokovic during the Australian Open final? In an epic match against Rafael Nadal — stretching to almost six hours before Djokovic prevailed — he was furiously crossing himself in the last minutes, and shouting prayers to God that appeared a mix of both aggression and desperation. As far as I could tell, Djokovic’s public piety went entirely unremarked.

As one who occasionally neglects prayers in the midst of a committed sedentary life, it is impressive to me that athletes with lungs burning and muscles aching take a moment to pray. On the other hand, physical exertion and psychological pressure do often bring one to the limits of stamina, and at one’s limits the religious believer is almost automatically inclined to pray.

Former Notre Dame football coach Lou Holtz, a practising Catholic not shy about his faith, was once asked what his teams would pray for before a game.

“Usually you pray for togetherness, for overcoming problems and for each other,” Coach Holtz explained. “We never, ever prayed for victory. I felt that that had to do with preparation and doing the things you needed to do, but we were just thankful. I think that when we prayed, we acknowledged greatness. We confessed the things we’ve done wrong. We give thanksgiving for the things we’ve had, the opportunity to play the game, the opportunity to be at this school and the opportunity to be associated with the various people. We’re thankful for our family. And then, of course, what we hope for is to help us realize the potential we have and to be able to live up to the talents that (were) given to us.”

As chaplain of our football team at Queen’s University, that is more or less how I lead team prayers too. I don’t pray for victories either, as our coach, like Lou Holtz, does not believe that is proper to pray specifically to win.

That view proceeds from a noble ideal, and I respect it. Yet I am not opposed to praying for success on the field or court or rink. We can hold up to God’s providence the desires of our heart, and that it is a worthy thing. And we often do desire to win.

Does God care who wins a football game? Is God on one team’s side? Put that way, the answer is clearly no. But God does care about what we care about. Sincere people object that to pray to win is, in effect, praying for others to lose, and that prayer cannot be pleasing to God. There is something to that. Yet there is often a dimension of that in many prayers of petition. Praying for admission to university means, in effect, that you and not someone else will get a particular place. Praying that Granddad gets admitted to a nursing home means, in effect, praying that one of the current residents dies soon to free up a room. Those prayers can be made sincerely though, offering to God our good desires and aspirations, and leaving it to the mystery of His providence how they may or may not be brought to fruition.

The story is told that Holtz was asked directly, when coach of Notre Dame, whether God really wanted Notre Dame to win.

“No, God does not care whether Notre Dame wins,” Holtz conceded. “But His mother sure does!”

Prayer, sport and whose side is God on?

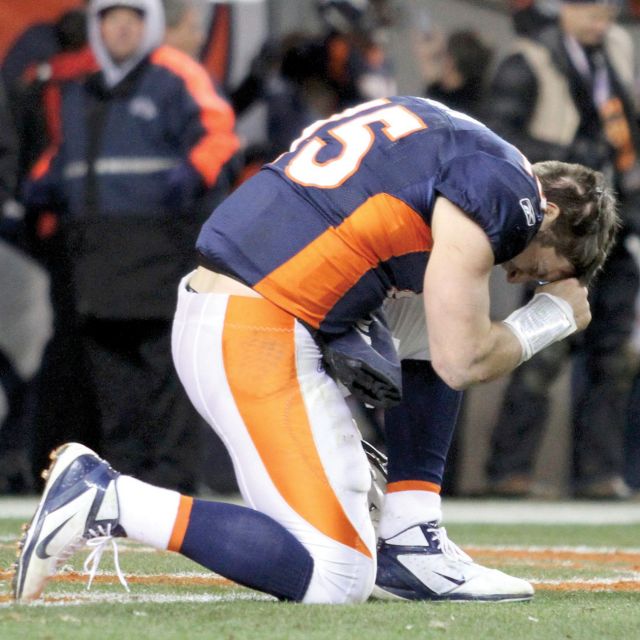

By Fr. Raymond J. de SouzaSuper Bowl Sunday marks the end of the football season and a look back at the year that was. On the field it was the year of the quarterback, with Drew Brees, Tom Brady, Matthew Stafford, Eli Manning and Aaron Rodgers all putting up eye-popping numbers. Off the field, the chatter was about one quarterback, Tim Tebow of the Denver Broncos.

His improbable story was captivating enough, coming off the bench in mid-season to lead his team to the playoffs with one last-minute victory after another. It was his Christian faith, though, that sparked an international discussion about whether faith had a place in sports, whether God was on Tebow’s side or whether Tebow thought God was on his side, or whether in fact God thought He ought to be on Tebow’s side.

Please support The Catholic Register

Unlike many media companies, The Catholic Register has never charged readers for access to the news and information on our website. We want to keep our award-winning journalism as widely available as possible. But we need your help.

For more than 125 years, The Register has been a trusted source of faith-based journalism. By making even a small donation you help ensure our future as an important voice in the Catholic Church. If you support the mission of Catholic journalism, please donate today. Thank you.

DONATE