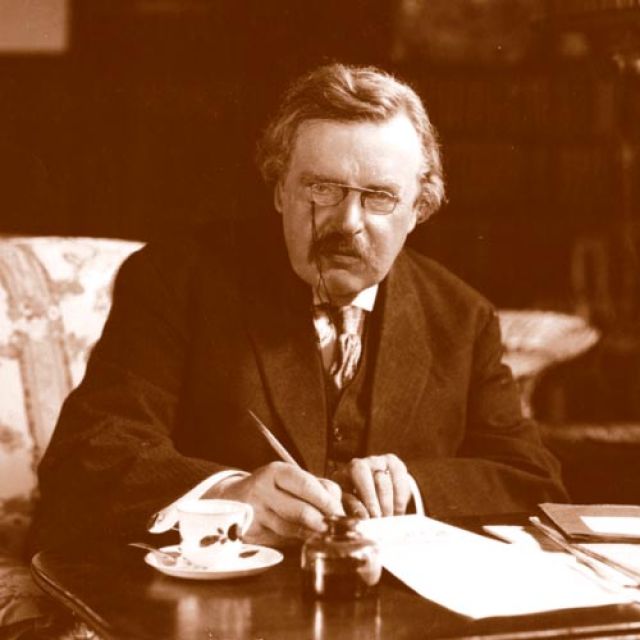

In his essay “The Case for the Ephemeral,” G.K. Chesterton argued that the fatal flaw of modernism was the meanness of its meaninglessness.

“It is incomprehensible to me that any thinker can calmly call himself a modernist,” the great Edwardian journalist wrote. “He might as well call himself a Thursdayite.”

The philosophical feebleness of modernism should discredit it for any thinking person, Chesterton said. Anyone with a heart should regard it with disdain, he added, because of its groundless contempt for those it opposed.

“The real objection to modernism is simply that it is a form of snobbishness,” he wrote. “It is an attempt to crush a rational opponent not by reason but by some mystery of superiority, by hinting that one is specially up to date or particularly ‘in the know.’

“To flaunt the fact that we have had all the last books from Germany is simply vulgar; like flaunting the fact we have had all the last bonnets from Paris. To introduce into philosophical discussions a sneer at a creed’s antiquity is like introducing a sneer at a lady’s age. It is caddish because it is irrelevant.”

Substitute the word “moderate” for “modern” in those century-old sentences and you have a mirror to hold up against much of what passes for political punditry in 2012. During the past two decades, society-shifting debates have been won by advocates whose primary skill has been donning the fashionable bonnet of “moderation,” regardless of how empty-headed their propositions and arguments might be.

A dizzying number of journalists have gone along with the ruse. Rather than asking how a societal change as radically transformative as gay marriage could be a moderate social modification, for example, they simply adopted the meaningless rhetoric of moderation.

When we read, hear or watch contemporary political commentary, as a result, we need a translator to tell us that: the word moderate is now a synonym for my — as in “whatever lines up with my beliefs”; the word mainstream is now a synonym for me — as in “whoever thinks like me”; the word modern is now a synonym for mine — as in “the latest fashionable opinions that coincide with mine.”

In other words, today’s media political-think is much ado about my, me, mine. Or as Chesterton put it in 1909: “The pure modernist (read: moderate) is merely a snob; he cannot bear to be a month behind the fashion.”

The pure Leninist would at this point ask: “What is to be done?” The undistilled liberal would ask: “What’s wrong with that?” The vintage Chestertonian asks a very different question: how was G.K. so perspicacious as to be so prescient about so much?

“There was a prophetic element in Chesterton,” says Fr. Ian Boyd, a Canadian Basilian priest based at Seton Hall University in New Jersey, where he edits the Chesterton Review and presides over the G.K. Chesterton Institute for Faith and Culture.

“His aphorisms and writings often suddenly illuminate a current problem. He was like a human seismograph sensing the rumblings of what was going to happen.”

A deep cultural rumbling Chesterton recorded was modernity’s movement toward moral self-immolation disguised as moderate progress, he said. Boyd told me in a recent interview that as long ago as the early 20th century Chesterton was cautioning against consumerist culture’s capacity to destroy age-old moral truths and traditions.

“He warned that people should not be too preoccupied with totalitarian menaces such as socialism because the next great heresy was going to be an attack on morality, especially sexual morality. The locus of that would be Manhattan rather than Moscow,” he said.

“Chesterton was aware of structures and their importance. He understood that most people borrow their ways of thinking and behaving from the cultures they’re immersed in. If the culture becomes toxic, you find that people who 40 years earlier would never dream of approving of abortion suddenly can’t quite see what’s wrong with it.”

When a people cannot tell its traditions from next Tuesday, when they will believe their theology is indistinguishable from a theory they heard last Thursday, then a cultural toxicity is well and truly progressing through us.

If only modernists had paid attention when Chesterton made the case against their meaningless meanness 100 years ago.