With that as its primary focus, a group of American Catholic Republicans tried to present Centesimus Annus as an endorsement of the Friedmanite economics then fashionable with the Reagan-Bush and Thatcher governments. That was a distortion of the document’s teachings, one which nevertheless gained a wide hearing. Rather, the encyclical should be seen as the most detailed and balanced summary of Catholic social teaching ever given. That remains true to this day, even considering the significant additions provided in the teachings of Popes Benedict XVI and Francis.

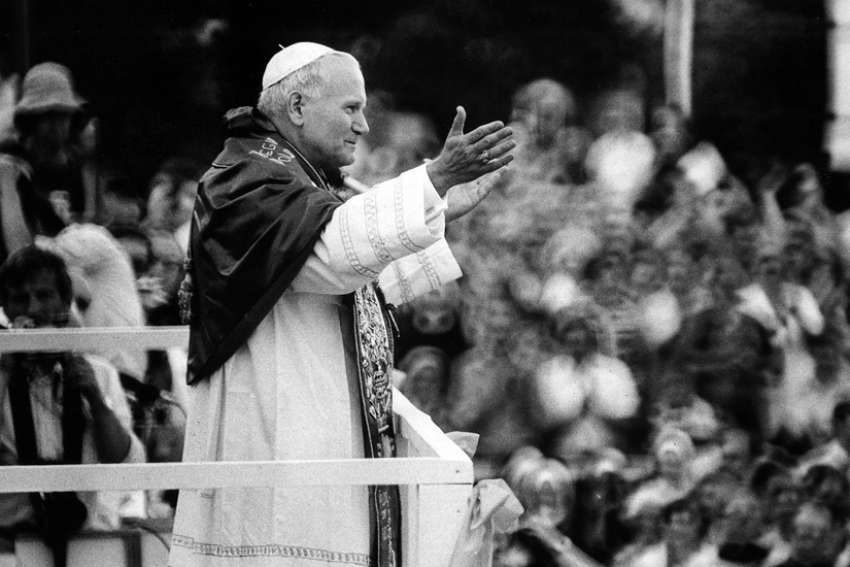

Catholic social teaching, Pope John Paul said, is not a model for economic and social development. It is rather “an indispensable and ideal orientation” that should help to shape models which must be developed in ever-evolving historical situations. Catholic social teaching provides an ethical foundation for the direction of society which nevertheless must be developed by the pragmatism and compromise of everyday politics.

Communism failed because it was an atheistic system which ignored the transcendent dignity of the human person. A political system which upholds that dignity will defend a conditional right to private property, the rights of workers to form unions and be paid a just wage, and the decentralization of power so that decisions are made at the most appropriate level of society.

A free market is the best way to organize society to distribute goods and services which have commercial value, but many essential human needs cannot be satisfied in the marketplace. The state then plays a crucial role in controlling the market so those non-commercial needs are met. The pope also urged society to place greater trust in the human potential of the poor and to give the marginalized the resources they need to make a positive contribution to economic prosperity.

Pope John Paul was equally critical of the consumerism of the West. Consumerism, too, is founded on a practical atheism which damages people’s physical and spiritual health.

New needs which arise in society must be distinguished from “artificial new needs” created to turn a profit while undermining the dignity of the person.

“One must be guided by a comprehensive picture of the person which respects all the dimensions of his being and which subordinates his material and instinctive dimensions to his interior and spiritual ones” (36).

A native of Poland who had vast experience in confronting the inhumanity of communism, Pope John Paul was also keenly aware of the deficiencies of Western societies. While a spiritual crisis was imposed on the people of Eastern Europe, the spiritual crisis of the West is one of supposed freedom. Massive corporations block the path of justice and treat people as objects rather than as subjects.

Where does this leave us today? First, the pope noted that the collapse of communism owed much to the success of “the Gospel spirit in the face of an adversary determined not to be bound by moral principles” (25). The triumph of the people was born of trust in God and widespread Christian devotion. This is a “political strategy” disregarded in the West. Our religiosity too often boils down to practical attempts to protect the Church’s institutions and efforts to marshal the Church’s remaining power to support dubious political ideologies. But if you take Pope John Paul seriously — and I do — a nation at prayer is a nation that will strive to protect human dignity.

Second, the clamour for individual freedom is growing louder and threatens to outstrip commitment to the common good. Many people believe, for example, that the requirement to wear a mask during the pandemic infringes on their civil rights. That’s an ideology which Centesimus Annus does not favour. The encyclical contends that individual freedom is qualified by the good of the community.

Thirty years after its release, Centesimus Annus is more relevant than ever. It doesn’t provide a sketch of how to organize society; it does offer a moral outline for respecting the transcendent dignity of the human person.

(Other recent writings by Glen Argan can be found at glenargan.substack.com)