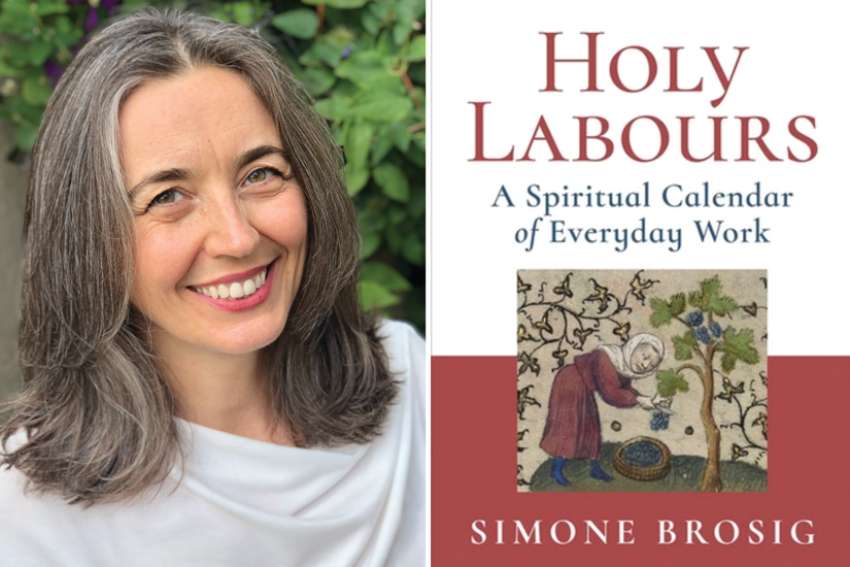

I begin this way because, as a cradle Catholic, liturgical practices have always felt mysterious beyond understanding and not a little scary, and those who understood it seemed to wield a terrifying power. Over the many decades I’ve spent organizing religious ceremonies connected to higher education, the liturgical architecture of an event or Mass was always slightly out of my comfort zone. It is the work of a true specialist. And a recent book published by Novalis is written by one such expert, Dr. Simone Brosig, formerly the Director of Liturgy at the Diocese of Calgary.

Holy Labours: A Spiritual Calendar of Everyday Work is the type of book that I have always secretly wanted, even though I didn’t know it. This is a practical guide, divided into the months of the year, that walks us through the sacred side of liturgical practice, but just as importantly, and as Bishop William McGrattan explains in the foreword, that shows us how this connects fundamentally to our everyday existence, so that “both the religious and secular nature of liturgy are united in celebration and praise of God who is at work within the wholeness and also the incompleteness of our lives.”

It is probably the case for many that we assume, at times, that we leave our ceremonial and spiritual practices behind as we leave the Church. For me it was always important, therefore, to be conscious of how the message of Jesus attended all my daily practices, secular and non-secular.

Holy Labours makes clear the connections between the sacred and the everyday in a way that is positively joyful. Here our “sacred labours” are shown to enrich our “daily labours,” to shape them and give them deeper meaning. As Brosig points out, such calendars are “nothing new,” though we tend to be more familiar with them in a medieval context.

In the Middle Ages, the Book of Hours was essentially a prayer book that everyday people could consult and structure their lives around. They have been called the “bestseller” of the day and tens of thousands of these books have survived to contemporary times. These devotional texts were occasionally or minimally illustrated, providing Church feast days, the four Gospels, the litany of saints and more. For wealthier patrons these books could be lavishly illuminated, often incorporating well-known landscape features known to the elite. There are also examples of the volumes being prepared to serve specific religious orders, even editions uniquely designed for women.

One of the most remarkable features is the incorporation of the monthly schedule of agricultural labour that functions as a type of Farmers’ Almanac, and as Brosig notes, the “substantial amount of real estate given to these ‘labours of the months’ on the pages of a book of prayer points to an appreciation of the sanctity of work; it also provides a visual testimony to the integral relationship between liturgy and life.”

For those who didn’t have a volume of their own, they could witness images of their labour inscribed in churches and stained-glass windows, and as Brosig makes clear, “the presence of the motif of the labours of the months in a religious context suggests that medieval Christian society considered manual labour dignified and the people who performed it sacred. After all, Jesus was a carpenter!”

The charm of Brosig’s book is that it honours this philosophy and adapts the Labours of the Month to reflect contemporary practices that we, in our own time, can incorporate into our days. Whether it is through the act of cleaning or remembering, mentoring or interceding, here is a guidebook to help us navigate our complex daily lives, and to do so through a language that is both divine and quotidian, reminding us that ultimately all life is sacred.

Another feature I especially appreciate is the structure of each section that unpacks and even decodes some of the mysterious elements and meanings of some of the rituals so many of us undertake, at times without fully appreciating their true complexity, in the process making the liturgist slightly less intimidating. And this work is brave and moving in other ways, offering a context for some of the chapters through the author’s personal experiences, such as her mother’s vascular dementia, details that further humanize the work of the everyday and how we can turn to our faith life to cope, communicate and better understand each other.

In the end, the book reminds us of one other important fact: that we need to live the liturgy, not just perform it. As Brosig wisely puts it, “Prayer is not complete until we have acted upon it. Our faith is meant to transform us to be more like Jesus in our behaviour toward God, others and ourselves.” I think we can all give an amen to that.

(Turcotte is president of St. Mary’s University in Calgary.)