On a recent Saturday at St. Peter’s Seminary in London, I was with a group that included men preparing for the permanent diaconate. It was an honour to share with them my vocation —living and giving witness to the social teachings of our Catholic faith. They saw everything that burns within me.

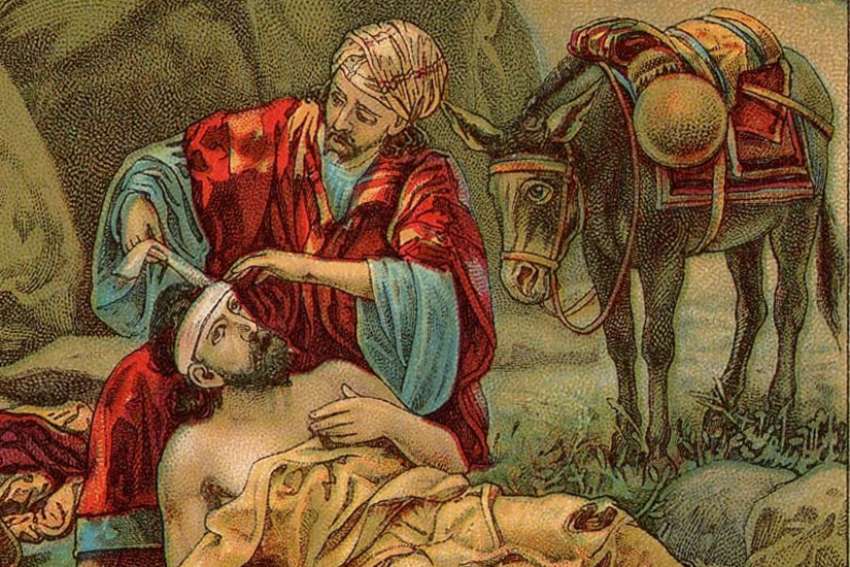

We opened the Scriptures to see how Luke (the evangelist) tells the story of the time that Jesus gave us the greatest commandment. In Luke’s version (Luke 10:25-37) the lawyer poses a further question, “and who is my neighbour?” What Jesus replied shocked His listeners.

In our culture, Good Samaritan refers to the simple imperative to be a good neighbour and take care of others, no matter what. The priest and the Levite were too focused on being pious and pure to be the neighbour God wants us to be. As a child, I though the only significant thing about the Samaritan was that, unlike the priest and Levite, he was an ordinary guy who would not have been expected to help. I did not learn until much later that Jews and Samaritans hated each other.

“If we were telling the story of the Good Samaritan today,” I asked the group in London, “who would the Samaritan in the story be?”

“A Muslim in a hijab from the Middle East.”

“A drug addict.”

Such were the replies. Here, I would up the ante even further and touch a Catholic cultural nerve: the abortion activist — any person who does not hold Catholic values when it comes to the vitally important issue of the dignity of the unborn.

Suppose we found ourselves on the road to Jericho that day. Suppose we happened upon the Samaritan as he attended to the wounds of the man who had been stripped, robbed, beaten and left for dead. What if the Samaritan asked us to help and asked for money to add to his own so the beaten man could be put up at the inn. How would we respond?

It’s easy to believe we would help. To us, the Samaritan is no one in particular. But what if it was not a Samaritan, but a leader in the pro-choice movement? Might we hesitate to help?

I can imagine what might go through our minds. What if we are seen? People would think I am helping an abortionist! What if they saw me give him money? We would worry about our picture being taken and splashed across the digital media landscape. We may be legally innocent until proven guilty, but on the Internet it is guilty once googled. We scorn the purity concerns of the Jews in the parable as obstacles to love of neighbour, but are our own purity concerns really so different?

Hopefully, we would help, no matter who needed our assistance. Hopefully we would put our very real differences aside for the sake of the one left for dead. Hopefully, like the Samaritan, we would be “moved with pity.”

The Greek word used in Luke’s Gospel for “moved with pity” is splagchnizomai. The noun form of the verb, splagchna, referred to the inner organs. So the verb is literally feelings in the gut.

So if a decision to help our “Samaritan” was questioned later, we might say we felt in our gut it was the right thing to do.

This reflection on the Greatest Commandment and the Good Samaritan is not only about who we should help but also how we should help them. If it is shocking to hear Jesus say the Samaritan is our neighbour, it is even more shocking that we might be called upon to co-operate with the Samaritan to meet the needs of the poor and oppressed.

Jesus does not suggest that we must accept or adopt the beliefs of the Samaritan. He does not say that to be a neighbour, you have to become a Samaritan. He simply says we are called, by the feeling placed in our gut by God, to respond to injustices against other humans and the suffering that it causes. And we should let nothing get in the way of that feeling, as it did with the priest and the Levite.

When we are moved by that feeling, Jesus says everything we think we know will get turned on its head. In our gut we know that God places no boundaries on who may work together to be a neighbour to the one left for dead on the road to Jericho.

(Stocking is Central Ontario animator with the Canadian Catholic Organization for Development and Peace.)

"Blessed are the merciful, for they shall obtain mercy." Matthew 5:7

Courtesy of Providence Lithograph Co.

Everyone in the group knew the greatest commandment. Love God, love your neighbour. Simple to say. Hard to do.