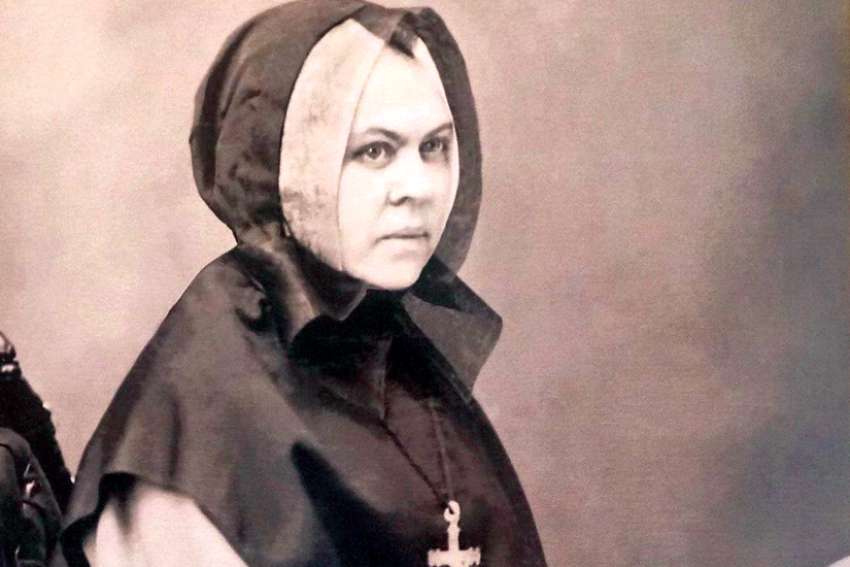

Thankfully, Michael McBane has not written a typical hagiography. To begin with, Elisabeth Bruyère is not a saint, though Pope Francis declared her Venerable in 2018.

Over the 300-plus pages of Bytown 1847: Élisabeth Bruyère and the Irish Famine Refugees, we learn a little about Bruyère, much more about the Irish famine of 1847 and a great deal about Bytown — the frontier lumber town that preceded Ottawa. Most of all, we are challenged to think about how this 19th-century Irish cataclysm shaped the Canada we live in now.

By 21st-century standards, Bruyère was barely an adult when she was sent to Ottawa with instructions to set up a school, an orphanage, a home for the aged and a hospital. She was 27. She had three younger Grey Nuns along to help her — girls she had mentored when they were novices.

Bruyère and her sisters accomplished all of their assigned tasks despite walking blind into a combined typhus epidemic and refugee crisis.

Nearly 7,000 Irish landed in the Ottawa Valley in 1847. They were part of a mass exodus of Irish during the an Gorta Mor, the Great Hunger. That displacement of at least three per cent of Ireland’s population killed 20,000 Irish peasants on their way to Canada in coffin ships, or soon after their arrival.

Passage to Canada was the cheapest and thus Canada was the first choice of the weakest, hungriest and poorest of Ireland’s displaced. Those who made it this far were quarantined at Grosse Isle in the mouth of the St. Lawrence River. From there it was on to fever sheds in Montreal, Toronto and raw, rough, tiny Bytown.

Bruyère won the contract to build and run a hospital for the refugees, whose sickness and vulnerability only grew once off-loaded as human cargo in Canada. She and her Sisters didn’t get the job because they were cheaper, more efficient, more experienced. There was nobody else.

They got the gig because they were willing to die. They expected to die and were surprised when they didn’t.

Unsurprisingly the town loved the Sisters, especially the poor Irish immigrants of Lowertown. But the English, Protestant establishment that ran the Uppertown didn’t love them. They conspired to deny the Sisters payment on the contract they had signed with the colonial government giving them charge of caring for Irish refugees dying of typhus.

Bytown wasn’t much in 1847. There were 5,000 people sharply divided by class, religion, language and country of origin. When Bruyère arrived, she and her Sisters had to establish a hospital because there wasn’t one. There wasn’t even a police force, and it was a rough place awash in alcohol and lumberjacks.

The corruption of the ruling elite, which regarded the colonial administration as its own piggy bank paying out in the form of government concessions and contracts and land, was mirrored by corruption on an even grander scale in the English administration of Ireland. The famine and consequent refugee crisis were understood at that time to be an artificial creation of large landholders with seats in the British Parliament who chose to impose a kind of plantation economy on their Irish colony, producing food for international markets and moving cotters (peasants) off the land.

Emigration was the preferred solution of the entrenched powers of British colonial rule, a policy which was at the time called “shovelling out paupers.”

But this isn’t just Irish history. The famine is Canadian history, too. Even if the vast majority of Irish who came to Canada in those years actually left pretty quickly for the United States, the crisis of 1847 advanced the argument for responsible government. Responsible government was what William Lyon Mackenzie and his fellow rebels were fighting for when they rose up against the Family Compact administration in Toronto in 1837. They lost.

But in 1847 the destitution, desperation and injustice Irish arrivals suffered at the hands of the English elite on both sides of the Atlantic made the argument once again that Canada needed to be a society less divided by class, less controlled by people born into money and power, more capable of knowing and acting on the common good.

Bruyère and the Sisters of Charity were part of that awakening in pre-confederation Canada, because they demonstrated it was possible. They created public institutions in health care and education that served the poor first and helped build a society that was less a gift bestowed upon people by the few and more a tribute to the dignity, hard work and hope of immigrants, workers and farmers.

Throughout Bytown 1847, McBane builds his picture of the year of crisis and Bruyère’s response by drawing on the work of Irish-Canadian journalists at the Bytown Packet and the Quebec Gazette of the 1840s. Canada at that time was living out its democratic spirit in a free press — a press that could question and challenge the corruption of the colony’s ruling class.

This was the promise of Confederation — responsible government and a common project to build a better, more inclusive society. Canada was born out of pain, loss and tragedy. But at the same time we discovered trust and solidarity because Bruyère and her Sisters were there to show us the way.

See also: