It’s not just that we are distracted, self-absorbed or inattentive. It’s not only that we hear distortedly when we aren’t aware of our emotions or our souls. It’s also dangerous to listen, because when you listen you might hear things. Switching off the ears of our hearts can be a defensive manoeuvre, like switching off the hearing-aid when the table talk gets boring or unpleasant.

A young woman told how painful it was hearing a friend’s account of protecting herself from the unwanted advances of a priest. It was unbearable, not because she didn’t understand or didn’t believe her friend — she cared deeply about the friend — but because it’s naturally distressing for the human heart to learn about evil deeds. We don’t want to hear. And often we shouldn’t listen, as with gossip, or don’t need to, as with Internet clutter. But sometimes we must, and then how do we bear it?

To listen is to risk heartbreak. Our hearts must break when they encounter the suffering of another, the abyss of pain that is behind every face. We have many ways of building forcefields around our listening hearts, to protect them from such heartbreak; some ways are healthy, some harmful to ourselves and some dangerous to others.

As a friend noted the other day, only half-jokingly, “that’s why I don’t go out of the house anymore.”

Not listening may be more of a human problem than merely a contemporary one, even if our distraction-laden lives make us more susceptible to the contagion. It’s likely that Jesus was highly accustomed to not being listened to; recall, for instance, His surprise at the young man who queried Him about the greatest commandment and then commented wisely on Jesus’ answer. Was Jesus frustrated by people’s constant inability to hear Him, each other and anything of depth or truth?

British comedy troupe Monty Python neatly parodied the problem as they imagined people in the back rows at the Sermon on the Mount, wondering why Jesus should bless cheese-makers.

“Humankind,” poet T.S. Eliot summed us up, “cannot bear very much reality.”

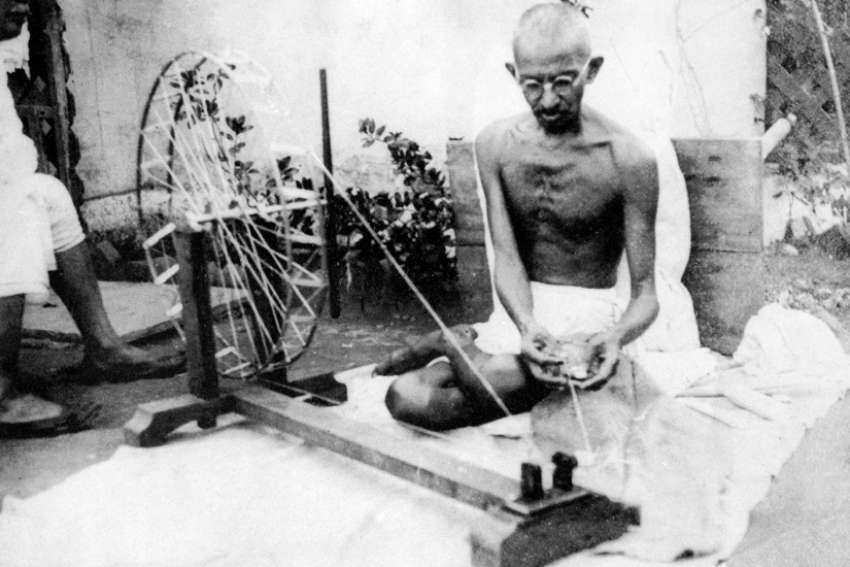

When Mahatma Gandhi was asked, the day before his murder at the age of 78, whether he stuck to his desire to live to 125 years, he responded: “I have lost that hope because of the terrible happenings in the world. I don’t want to live in darkness.”

It is not only painful to listen too much; it is unbearable. Even the greatest among us are too small, yet, for all that is. Too much darkness breaks us apart. Maybe too much light does, too.

All are called to listen. Could it be that listening requires knowing one’s measure? The measure in which we can listen is often shaped by sin in us, because sin puts a limit on love and listening. Nobody listens to everything, unless they are God who promises to listen to the sound of a toe stubbed against a stone, or a sparrow’s feather whisping to the ground (see Psalm 91 and Luke 12).

Learning to listen is also becoming more and more like God. If we listen just where and when we are asked to, we may find our capacity for listening stretches and grows, without destroying us.

One of the great Christian Scripture scholars, Origen of Alexandria (d. 253), wrestled with the many ways one can listen to the Scriptures. Which is correct? Origen answered by his lifetime of ground-breaking Scripture studies, including creating the first parallel Bible in six columns of different translations.

To spend time with Scripture, to read, study, pray with the Scriptures, Origen taught, is to become increasingly open and aware of their hidden meaning. They open up to us as much meaning as we can hold.

Scripture is inerrant, not because it never makes mistakes or contradicts itself, but because it unerringly holds out the truth of God to the open heart. Listening — to God, to reality, other people, ourselves, our world — is not a performance. It’s a movement, an ever-larger place we spend our lives walking into (see Psalm 18:36).

What, then, is the measure of our listening? Whether to God in Scripture, in the Church or in prayer; whether to others, ourselves or all of creation; what is the measure? God, who is infinite, listens infinitely. We, who are made by God, must find our own measure. It’s the tension point between who we are and who we are becoming on our way to eternity.

The young woman who listened to her friend’s pain and was asked to hear the story of an evil deed in a sacred place did so out of love for her friend and for the Church. If Gandhi couldn’t bear 125 years of human darkness, he did bear the life of God to such a measure that his last breath on Earth was a cry to God.

What is the measure of our listening?

(Marrocco can be reached at marrocco7@sympatico.ca)