At camp, we see the children brought to life by connecting with forests and rivers, stars and night darkness and feel of the bare earth. They also are full of fears: fear of the unknown, or their own inner fears, and fear of the real dangers that the outdoors present.

Domination, ignorance, abject fear are clearly wrong relationship between humans and the natural world. What is right relationship?

Present-day worries about weather and confusion about the proper relationship of humans to animals put such questions in public discussion. André’s assessment highlights a paradox, that a culture highly conscious of its connection with nature should at the same time suffer from disconnection with it. Children need to learn how to be in nature, but who can teach them?

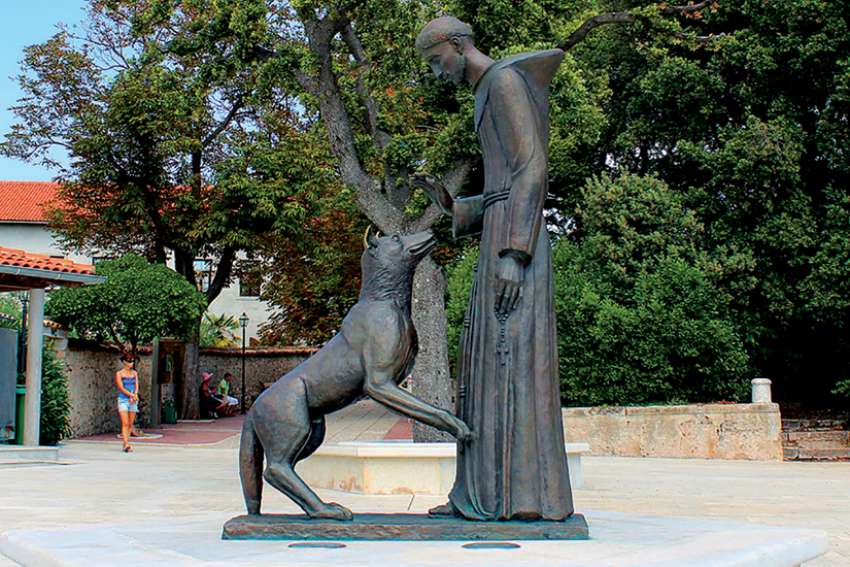

Perhaps you, like me, learned as a child from St. Francis of Assisi. His love of and communion with nature have made him one of those rare saints who are beloved of everybody, Christian or not. Francis didn’t sentimentalize nature; he didn’t love it from a distance, or virtually. He knew it personally, delighted in it, but respected its dangers.

When his neighbours needed help with a vicious wolf who was terrorizing them, Francis understood their fear and took it seriously. He didn’t expect them to simply put up with its behaviour as “natural,” knowing they needed to protect themselves.

The ensuing story of Francis and the wolf of Gubbio may seem fantastical to us, if we think of him as conversing with it and taming it like Disney’s Cinderella with the mice. But the reality, the creativity and courage of his response comes from his awareness of how things really are, and his willingness to stake his life on it.

We need to learn to be in reality, with everything that surrounds us. There’s no point behaving as though there were not a rupture between and within nature that affects us all. “Nature, red in tooth and claw,” can hurt us, and we can hurt it. This disjunction exists because of sin — not nature’s sin, but ours.

Somehow, when humans turn deliberately away from God, they also harm their relationship with the created order and harm its internal relations, too. Nature suffers when humans turn their backs on God. This is what current ecological ideas often ignore.

Yet we hold a treasured memory of peace with and among the animals in the Garden of Eden (Genesis 1), and a corresponding vision of peace to come: “Then the wolf shall be the guest of a lamb” (Isaiah 11:6).

Stories of saints’ lives show a radical, even unearthly harmony with nature. Like Ambrose of Milan, who had a swarm of bees land on his baby mouth and leave honey behind.

Are such stories pious sentimentality? Do they reflect how our relationship with nature is changed by sin and reworked by repentance, forgiveness and faithfulness?

When we listen to God, there is no fear in our hearts. When we have trouble listening to God, we become afraid; and then the animals get afraid also and nature is broken, too. This kind of fear came into the world because Adam and Eve didn’t listen to God, and each of us continues to let fear in when we close our ears and hearts.

Francis meets the wolf and gets him to stop harming people and animals in exchange for being welcomed and fed by the villagers. Francis’ presence heals fears — the people’s and the wolf’s. Their new relationship reflects paradise and images Heaven.

How could Francis accomplish all this? Because he had cast off fear for the sake of love. He turned his face to the poorest and most vulnerable, and radically changed his own relationship to the physical world.

Our own Francis (Pope) reminds us that the poor are the ones who suffer when the Earth suffers. Issues of ecology, he says, are urgent not because of inconvenience to the wealthy, but because of the great suffering of the dispossessed. That is why failing to care for creation dishonours God, for God’s image is at the centre of all creation.

Francis of Assisi goes beyond fear to meet the wolf, not for his own gain but for the sake of his suffering neighbours — and their fears are healed, too. No violence is required from anybody. This is a vision of paradise — and Heaven.

When we meet our fears this way, they become allies instead of enemies, like the wolf and the villagers. It’s not a magical snap of the fingers making a shiny happy ending, but a work of love, which can risk all for the sake of the vulnerable.

(Marrocco can be reached at marrocco7@sympatico.ca)