Madame Odessi Petit Foin knows exactly what she’s missing since the church in Duvale collapsed, along with her house and most of the other houses in the farming community.

Duvale always did need lots of things. It was never rich. It needed a new road before the earthquake and now it needs it more. It has needed a new school for a long time and thanks to the earthquake it got one — built with aid money on the foundations of the collapsed church. And it needs houses for the families still living in tents by their tiny plots of tomatoes, cucumbers and peas.

In Petit Foin’s opinion, Duvale also needs its church.

“It preaches morality and conversion,” she said.

She also makes the point that it’s through the church that Duvale gets access to the international aid money which will finance a new Caritas Port-au-Prince agricultural improvement project. But that’s not the most important reason that Duvale needs its church.

“The church in Duvale plays a very big role that holds together friends and family,” she said.

Petit Foin is not an economist, a politician, a theologian or philosopher. But as she stands in the old church hall, which has become the church in Duvale, she’s hit upon something quite important.

There’s more to infrastructure than the efficient delivery of goods to market on safe, smooth and broad roads. A community requires infrastructure so it can hold together, so it can know itself and meet the world. Duvale needs its church so that it can be a community which people recognize when they see the church.

The people of Duvale themselves need to recognize that they are a community of families when they meet for Sunday morning Mass.

There is such a thing as spiritual infrastructure. In fact, if Duvale had a great road connecting it with Port-au-Prince but its people had lost their way and no longer knew themselves, no longer cared for each other, no longer lived in and for their families — well, that would be a road to nowhere.

- RAISING UP HAITI -

a Catholic Register special report

Haiti's churches need healing [slideshow]

What now in Haiti?

Post-traumatic stress proves difficult

Catholic aid organizations fly under the radar

Canadian engineer to oversee Haiti’s Church rebuild

Haiti must take this opportunity to change

Crisis makes D&P rethink how it operates

Bold education plan held up by a lack of funds

Church holds community together

D&P-funded program provides pro-life solution to Haiti's sexual violence

Haitians must look to themselves to rebuild their nation

Bold education plan held up by a lack of funds

By Michael Swan, The Catholic Register

For the first time in St. Antoine’s history the teachers are worried about their girls in Grade 6. Before the Jan. 12, 2010 earthquake 100 per cent of Pupils de St. Antoine students would pass state exams that qualify them to move on to Grade 7 and secondary school.

This year most of the girls are living in tents on the Champ de Mars. Before the earthquake there were 700 students, now there are 570. Many of the parents are having trouble coming up with $180 for school fees, to say nothing of books and uniforms. Development and Peace is helping by paying for hearty lunches of rice and beans with vegetables and meat. The girls are eating better than their parents.

The girls’ biggest handicap is the loss of their school building, according to school principal Sr. Sainte-Anne Jean-Baptiste. The old St. Antoine’s is a heap of rubble and the Sisters of St. Anne have no money to clear it and rebuild or to buy another site.

“The education we want to give children we can’t give right now. They need to progress — to go from one success to another,” said Jean-Baptiste. “It’s almost impossible to study in the tents.”

St. Antoine’s is borrowing the classrooms of Cole Marie Reine Immaculate. When that school lets out in the afternoon, St. Antoine’s moves in. But St. Antoine’s has no offices, no meeting rooms, no equipment, nothing but the classrooms — many of which are squares on the concrete courtyard walled off by sheets of plywood beneath a tin roof.

There are about 40 girls in every classroom. Their teachers also live in tents, though many are able to remain at the site of their old homes and thus are spared the crowded, fetid, cholera-breeding tent camps.

Veteran teacher Michelle Auguste believes in her students. “With education these girls will do anything,” she said.

Auguste isn’t talking out of pollyanna optimism. Her daughter went to St. Antoine’s and then high school at College Marie-Anne — both inner city Catholic schools whose students are mainly lower middle class and poor. She is now in second year at National Taiwan University studying physiotherapy.

Cecile Romiette Auguste speaks French, Creole, Spanish, English and Mandarin. She may pursue a Master’s degree after her undergraduate studies in Taiwan.

“Those who educated me in elementary school and high school, even if I might spend my life talking about them I don’t think I could ever describe to you half their worth,” the young Auguste wrote in an e-mail.

She visited home last summer and wept at the ruins of her old school.

“I believe strongly that a generation of women who graduated from St. Antoine can transform the fate of my country,” said Auguste.

Little of Haiti’s education system still stands. Eighty-nine per cent of the schools — including two universities in Port-au-Prince — were destroyed. The Haitian government has developed a $4.2 billion, five-year plan to cover education, but doesn’t have the money to implement it. Current government spending is around $80 million per year. The Inter-American Development Bank kicked in $50 million in November, and will contribute $250 million over five years.

The United Nations Development Program lists Haiti’s literacy rate at 62.1 per cent, but most observers think the real rate is just over 50 per cent. For Haiti to ever become a real, functioning democracy the literacy rate will have to rise significantly among the earthquake generation.

At Ecole Immaculee Conception Haiti’s future looks bright. The school yard is filled with happy, energetic girls rehearsing a dance for a school show. Annual fees are $500 and while these kids are not necessarily rich, they are less likely to be caught up in the tent camps than St. Antoine’s students.

Development and Peace has provided $350,000 to the Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Conception to build the second storey of a two-storey school. As construction on the earthquake-proof school proceeds, classes are held under tents.

The Sisters have put their students and the school ahead of their own comfort. While the hill-top site is host to a busy construction crew laying bricks and mixing cement, the nine Sisters are living in four old classrooms in the old school. All the community’s possessions, from clothes to books, are piled in an old box car nearby. Every Sunday between 300 and 500 people gather in the open space where the rubble has been cleared to celebrate Mass with the Sisters.

Sr. Josette Drouinard would love the new building to have an auditorium and chapel but there are no funds. Meanwhile she is proud of the new school under construction.

“It will be a functional building, but with all the comforts,” she said.

- RAISING UP HAITI -

a Catholic Register special report

Haiti's churches need healing [slideshow]

What now in Haiti?

Post-traumatic stress proves difficult

Catholic aid organizations fly under the radar

Canadian engineer to oversee Haiti’s Church rebuild

Haiti must take this opportunity to change

Crisis makes D&P rethink how it operates

Bold education plan held up by a lack of funds

Church holds community together

D&P-funded program provides pro-life solution to Haiti's sexual violence

Haitians must look to themselves to rebuild their nation

Crisis makes D&P rethink how it operates

By Michael Swan, The Catholic Register

In Duvale, an exhausting two-hour crawl by Toyota Land Cruiser from Port-au-Prince, the Caritas network is trying to pick up the pieces for local peasants.

Eighty per cent of the buildings in Duvale collapsed last Jan. 12, including the church. Port-au-Prince refugees from the earthquake wandered through the area in February and March and ate up all the seeds for the next crop. Even before the earthquake, farming in Duvale was far from profitable. The area’s poor soils yield pathetic crops.

With about $3.5 million in financing from the Canadian Catholic Organization for Development and Peace, Caritas Port-au-Prince will provide Duvale and seven neighbouring villages with an agronomist and an agricultural technician to test soils, provide advice and teach more sustainable farming methods. Donors are providing new seed. New wells will make water available for irrigation and other uses. It will be a five-year program starting this month.

Farmers will learn to terrace the land and other soil conservation techniques essential to successful farming in a country that is 70-per-cent mountains and disastrously bare of its trees.

An existing microcredit program, focussed on women, is being expanded.

Duvale is a classic example of the kind of work Development and Peace has done around the world over the last 40 years. It’s led by a local partner, based on the priorities of peasant farmers themselves, concentrates on women — who are proven to yield the greatest return on a development dollar — and brings the community together in self-sustaining, co-operative structures.

The trouble is the road. There’s no way any crops will get to market over the pathetic excuse for a road that separates the village from Port-au-Prince. Neither Caritas nor Development and Peace can build roads for the government of Haiti. Donor money doesn’t add up to the price of a real road.

A good development project of this kind will organize peasant farmers and embolden them to demand services from their government, including a better road. But in more than 200 years of independence, Haiti has never really had a competent government capable of delivering services to its people, or politicians interested in anything of the sort.

On the other hand, for the last 30 years the people of rural Haiti have pursued another development program without help or encouragement from development agencies. They’ve been moving to Port-au-Prince and the provincial towns, living in dangerous, overcrowded slums, looking for work and wages.

It’s a high-stakes gamble, and many wind up trapped in poverty on the edge of the city. But many succeed. Or their children succeed. Between 1975 and 2005 Port-au-Prince’s population grew by 269 per cent to 3.5 million.

Why do Catholic development agencies (it’s not just Development and Peace) favour rural development projects and abandon the slums to their fate?

It’s not an entirely fair question. Development and Peace does have some urban projects, and it has an even greater commitment to the lives of the urban poor in post-earthquake Haiti. But the established peasant farmers of Duvale, even in the wake of a disaster that has erased their homes and farms, are not moving to the big city.

“This is our home. This is our land,” explained Fritz Ner-Sérénium. “We were born here. What we want to see is this area developed. In Port-au-Prince we would have to do work we don’t know how to do.”

Of course the situation for 40-year-old farmers is not the same as the situation for their children. Duvale’s school goes to Grade 6. High school requires a move to Port-au-Prince. A high school diploma doesn’t really qualify anyone for a job, but it does set a young person’s sights higher than goats, chickens and a field of tomatoes.

“It’s very good to run good rural development programs, but don’t assume that this will necessarily keep people in rural areas,” said David Satterthwaite, a senior fellow at the London-based International Institute for Environment and Development, in an e-mail to The Catholic Register.

In the aftermath of the earthquake, Development and Peace finds itself engaged in programs very unlike the Duvale project and much more focussed on the urban aspirations of the next generation of Haitians. But executive director Michael Casey hesitates to say the $20.4-million program in Haiti represents a turning point.

“None of the regular rules, regular guidelines necessarily apply in a case like this,” he said.

The irregular, even novel efforts of Development and Peace in Haiti this past year have included posting a Canadian employee in Port-au-Prince to support, monitor and guide post-earthquake spending, funding religious communities rather than conventional NGOs and funding education.

Community development aimed at righting the scales of often brutal economies has been the core reason for Development and Peace’s existence. Education and social work are a responsibility of government. But ground rules that have applied in Haiti since Development and Peace was founded in 1967 crumbled with the earthquake.

“You try to respond where you best can. We had a network of religious communities that were actively involved in the types of things the society needs to get back on its feet,” said Casey. “We have a Caritas network in place that was very focussed at the community level.”

Casey foresees the exception of a huge disaster such as Haiti becoming the rule.

“We can’t just say we won’t get involved in emergency work because it’s not part of our development approach,” Casey said. “You can’t do long-term sustainable development of civil society organizations like we do if you don’t have roads and people are sick and buildings are destroyed.”

Development and Peace isn’t alone among NGOs in terms of having to rethink its role, said University of Toronto expert in NGOs Wendy Wong.

“It’s a moment of crisis for service providing NGOs in terms of rethinking their role in international politics,” she said.

Responding to the new reality may involve new ways of doing the job, including Canadian staff on site and in the field. Finding well established, well-run partners in urban slums to lead and manage projects may simply be impossible.

In Haiti the decision to break with tradition and place a Development and Peace staffer in Port-au-Prince was difficult.

“Will the presence of one of our northern staff, or expertise from Canada, add enough value to the process to be a benefit? We have to look at that,” said Casey. “These questions are on the table.”

The earthquake has changed Haiti. It may be that Haiti will change Development and Peace.

- RAISING UP HAITI -

a Catholic Register special report

Haiti's churches need healing [slideshow]

What now in Haiti?

Post-traumatic stress proves difficult

Catholic aid organizations fly under the radar

Canadian engineer to oversee Haiti’s Church rebuild

Haiti must take this opportunity to change

Crisis makes D&P rethink how it operates

Bold education plan held up by a lack of funds

Church holds community together

D&P-funded program provides pro-life solution to Haiti's sexual violence

Haitians must look to themselves to rebuild their nation

Haiti must take this opportunity to change

By Michael Swan, The Catholic Register

In 1983 Pope John Paul II put a scare into Haiti’s rulers. The pope stepped off his Alitalia plane and, disdaining the red carpet, the banquet and all the pomp Haiti’s royal household could muster, he kissed the ground and spoke directly to the people.

“Fok sa chanj!” he said in Creole from the airport tarmac. “Things here gotta change!” and the pope meant it.

Jean-Claude Duvalier and the ruling class would soon be gone, but things didn’t really change. The misrule of Haiti continued through two successful coups, several parodies of democratic elections, a U.S. invasion and an attempt at civil order by UN peacekeepers. Jean-Bertrand Aristide, the hope of the poor, ended his first presidency ruling by decree. His second presidency was spent blaming others for failures and funneling money to Washington lobbyists.

By the end of 2009, Haitians were still saying things had to change. But even an International Monetary Fund decision to cancel $1.2 billion in Haitian debt seemed unlikely to change anything.

Are the deaths of 230,000 Haitians in a magnitude 7.0 earthquake an opportunity for change? Is Haiti ready for a new beginning with its capital city reduced to rubble?

By March last year international donors had pledged $5.3 billion for reconstruction. Hopeful talk about “refounding” Haiti became common. But at the end of 2010 there were still more than one-million residents of the capital city Port-au-Prince living in tents, cholera was racing through tent camps and the first round of elections had produced rioting.

“We are fighting to build a new Haiti, but it’s a very long process,” Jean-Baptiste Chavannes, leader of the 60,000-strong Mouvman Peyisan Papay (the Peasant Movement of Papay), told The Catholic Register.

More than anything the political culture of Haiti has to change. A winner-take-all version of political leadership, often accompanied by violence — whether it was the paramilitary Tonton Macoutes of the Duvalier regime or the FRAPH attaches of Roul Cedras’ military junta — has poisoned Haiti’s history, said Chavannes.

“The mentality of the Tonton Macoutes is to have money and to have power,” he said.

The mentality of Haiti’s next leaders has to be something different.

“We’re trying to change the old mentality. It’s more profound, deeper,” said Yolette Jeanty, co-ordinator of the women’s rights organization Kay Famn.

“It’s not only building things.”

There was a spark of hope, an indication things could change, in the aftermath of the earthquake, said Jeanty.

“Right after the earthquake, people felt the need to come together,” she said. “There was an opportunity to have Haitians sit together and rethink, but leaders haven’t brought people together.”

A lack of leadership has squandered a precious moment when Haitians stood by one another, dug through the rubble together and shared what they had, said Jeanty. “It was an opportunity,” she said.

While outsiders often see Haiti as a violent and deeply divided society, the solidarity which broke out after the earthquake did not surprise Redemptorist Father Adonai Jean-Juste.

“Charity and love, it is a human value — not only for the rebuilding of Haiti,” he said.

But Jean-Juste also regrets how the sense of common purpose and shared destiny which arose from the earthquake has dissipated.

“We have to work hard to build a new Haiti. It won’t be given to us,” he said. “I believe in a new Haiti — maybe not next year, but we will make it.”

The most essential resource for a new, refounded Haiti is the determined, stubborn hope of ordinary Haitians, said Caritas Haiti spokeswoman Ridana Cornet.

“People from abroad are often surprised by the ability of people in Haiti to keep on,” she said. “Two days after the quake people were out and trying. There’s always the hope that things will get better.”

“The challenge for the many countries and organizations that are willing to help Haiti is to understand that they need to work with the Haitians and not dictate the way things need to change and improve,” said Dr. Peter Kelly, an American who has volunteered for many years in Haiti and helps run the Crudem Foundation’s Sacre Coeur Hospital in Milot.

If Haiti is going to be refounded, the important questions are “How and by whom and for what purpose?” said Haitian expatriate Guerda Nicolas.

Nicolas is outgoing president of the Haitian Studies Association and a professor of psychology at the University of Miami. She has been back in Haiti every month since the earthquake, working on development projects and taking part in official planning.

“I am very hopeful that the Haitian people are very, very strong and very, very resilient,” she said.

There is a role for Haitian ex-patriates, a role for people and nations of good will and a role for the Church in refounding Haiti, said Nicolas. “If you really want to get Haitians moving there are only two things you have to say to them. One is Church, Nicholas said.

“It’s really having an opportunity to connect with their priests and pastors, to hear from their priests and pastors. That has a lot of meaning for them. The second is to talk to them about how to get an education for their kids. Those two things will get Haitians coming out for any meeting.”

- RAISING UP HAITI -

a Catholic Register special report

Haiti's churches need healing [slideshow]

What now in Haiti?

Post-traumatic stress proves difficult

Catholic aid organizations fly under the radar

Canadian engineer to oversee Haiti’s Church rebuild

Haiti must take this opportunity to change

Crisis makes D&P rethink how it operates

Bold education plan held up by a lack of funds

Church holds community together

D&P-funded program provides pro-life solution to Haiti's sexual violence

Haitians must look to themselves to rebuild their nation

Canadian engineer to oversee Haiti’s Church rebuild

By Michael Swan, The Catholic Register The huge task of rebuilding the Catholic Church in Haiti will be led by a Canadian civil engineer and project manager who will oversee the first $100 million in construction over the next three years.

The huge task of rebuilding the Catholic Church in Haiti will be led by a Canadian civil engineer and project manager who will oversee the first $100 million in construction over the next three years.

Yves Lacourciere from Quebec will take over PROCHE, an initiative of the Haitian bishops to rebuild churches, hospitals, schools, a university and a seminary destroyed last Jan. 12 in the devastating earthquake that killed 230,000 people. PROCHE stands for Proximite Catholique avec Haiti et son Eglise or “Catholic nearness to Haiti and its Church.”

Lacourciere was to start the project with a four-day meeting with five Haitian bishops Jan. 7 to 10. The meetings are expected to end with an announcement of rebuilding priorities and broad timelines on Jan. 12, the anniversary of the earthquake.

“If the goal is to give hope to people in the country, to me it will be that we need to have an action spread throughout the country,” Lacourciere told The Catholic Register.

The earthquake destroyed 70 parishes, including the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Assumption in Port-au-Prince, dozens of schools, several convents and the national seminary, reported Catholic News Service. Three Port-au-Prince archdiocesan leaders —Archbishop Joseph Serge Miot, Msgr. Charles Benoit, vicar general, and Fr. Arnoux Chery, chancellor — died in the quake along with seven priests, 31 seminarians and 31 men and women religious.

Among the possible priorities for the rebuilding program will be building skills for development among Haitian workers, promoting women through employment in the project, drawing communities together by reconstituting churches, strengthening the bonds between the Catholic Church and Haitian society by repairing the hospital, university and other service institutions and reinforcing the Haitian church by rebuilding the college and major seminary.

Lacourciere estimates the total rebuilding effort will last 10 years and cost in the neighbourhood of $300 million.

The Quebec engineer with a masters in administration and a PhD in technology, estimates he has been in Haiti 20 to 25 times between the late 1970s and mid-1990s overseeing building projects. He has also worked in the Dominican Republic — the other half of the island of Hispaniola — and Qatar. Following the civil war in Yugoslavia, Lacourciere oversaw engineering and business start-ups in Kosovo between 2000 and 2004.

“I am not a specialist. I am a generalist,” said Lacourciere.

Being a native French speaker who can communicate directly with Haitian bishops and international diplomats will be an advantage on the job, he said.

“I’ve always worked on big jobs,” said Lacourciere. “But what I like with this job is that I can use a lot of experiences I have had in the past. I am more than 60 years old. So, what I want is that what I will do is not for the money. It’s for help. I’m sure that there (in Haiti) I will be able to help.”

- RAISING UP HAITI -

a Catholic Register special report

Haiti's churches need healing [slideshow]

What now in Haiti?

Post-traumatic stress proves difficult

Catholic aid organizations fly under the radar

Canadian engineer to oversee Haiti’s Church rebuild

Haiti must take this opportunity to change

Crisis makes D&P rethink how it operates

Bold education plan held up by a lack of funds

Church holds community together

D&P-funded program provides pro-life solution to Haiti's sexual violence

Haitians must look to themselves to rebuild their nation

Catholic aid organizations fly under the radar

By Michael Swan, The Catholic Register

Chances are that the first voices you hear in post-earthquake Haiti will have that self-assured twang of Southern Baptists from Houston, Atlanta, Tallahassee or Nashville. They land in bunches at Toussaint Louverture International Airport wearing T-shirts that read “Healing Haiti” and other rather proud claims.

They’ve come to be with the people of Haiti in whatever way they can. Many of them have real skills, from engineering to medicine to construction. They may be mostly unilingual and perhaps culturally tone deaf, but we should remember that the first Bible translated into Creole was a mostly Baptist effort.

Haiti is 80-per-cent Catholic, but Catholic visitors are rarely seen.

Catholics are there however, said American Dr. Peter Kelly.

“We need to do a better job of educating the world about all that Catholics are doing in Haiti,” he told The Register by e-mail.

Kelly is the president of the board of the Crudem Foundation which founded the Sacré Coeur Hospital in Milot. The hospital is supported by three American associations of the Order of Malta, and the board works closely with the Maltesers, the Knights of Malta’s international aid organization.

“There are many Protestant groups in Haiti and they are doing a good job providing health care and education,” said Kelly. “However, the Catholic presence in Haiti is much greater but doesn’t seem to get the publicity.”

Some of that may have to do with a preference for deferring to Haitian leadership and expertise whenever possible.

“Our philosophy has always been to teach the Haitian medical personnel to provide the best care possible for the Haitian people. We have been very successful in our goal and now have 20 Haitian physicians on staff as well as 90 nurses,” said Kelly. “We bring volunteers to our hospital to work side-by-side with Haitian staff providing care to the patients as well as teaching the Haitians and learning from them.”

The cholera outbreak in November was a case where Haitians took the lead. Volunteers simply couldn’t get into the country quick enough to help.

“Our Haitian administration developed an emergency plan for treatment of the cholera patients and became a cholera treatment centre,” said Kelly. “They did this without any volunteers present in the country, although we provided guidance. When the (Atlanta) Centre for Disease Control inspected our centre we were told that it was the best in the northern part of the country.”

When volunteers got there, it was Haitian staff who told them where to be and what to do.

“The challenge for the many countries and organizations that are willing to help Haiti is to understand that they need to work with the Haitians, and not dictate the way things need to change and improve.”

- RAISING UP HAITI -

a Catholic Register special report

Haiti's churches need healing [slideshow]

What now in Haiti?

Post-traumatic stress proves difficult

Catholic aid organizations fly under the radar

Canadian engineer to oversee Haiti’s Church rebuild

Haiti must take this opportunity to change

Crisis makes D&P rethink how it operates

Bold education plan held up by a lack of funds

Church holds community together

D&P-funded program provides pro-life solution to Haiti's sexual violence

Haitians must look to themselves to rebuild their nation

Post-traumatic stress proves difficult

By Michael Swan, The Catholic Register

Children, lost and disoriented, looking for a safe place after the earthquake found it in the courtyard of the Holy Cross Sisters. For more than a week the children were crowded in, occupying the driveway and the garden and reluctant to spend much time under the Sisters’ rather sturdy roof.

Of course they were troubled and traumatized, said Sr. Marie-Pierre Saint Amour. She didn’t need her training in psychology from the University of Ottawa to tell her that. She heard the children’s cries at night when nightmares woke them. She saw the angry face of the devil in their drawings.

Since then, Saint Amour has come to realize her whole country is suffering from a sort of mass post-traumatic stress disorder. She’s had some success treating the young people, but how do you administer psychotherapy to a nation?

“Everyone is focussed so much on the medical, but forgetting the psychological,” said Fr. Michel Martin Eugene, a Holy Cross priest and psychologist.

There are fewer than six psychiatrists in all of Haiti, Dr. Peter Kelly said. Kelly is president of the Crudem Foundation, which runs Sacre Coeur Hospital in Milot with the support of three American groups of the Order of Malta and Catholic Relief Services.

Kelly and other volunteer doctors in Haiti after the earthquake observed widespread post-traumatic stress syndrome. They also saw that most Haitian medical staff were reluctant to diagnose depression or PTSD.

“I believe it has something to do with their culture, as well as the fact that they have faced so many hardships throughout their history that they accept it as normal and move on with their lives,” Kelly wrote in an e-mail.

Unlike the doctors, Haiti’s religious see psychotherapy as an essential, missing piece of the recovery. Working with students in education and social work, the Psychosocial Support Network of the Haitian Religious Conference has created a program to help people face trauma that has often been ignored for months while they dug out their neighbours, tracked down lost family members, went back to work and managed life in a tent. In many cases, depression, anxiety and all-pervading fear hit people months after the earthquake, said Saint Amour.

“They never dealt with the trauma, then they are hit with a lack of energy, depression.”

“It’s a big crisis,” said Eugene. “They wander the street — broken people.”

Eugene’s assessment of the situation is rare among Haitians, who “are so stoic,” said Kelly.

“It is also difficult to institute training of Haitian medical personnel to treat this problem when they tend to deny its existence,” he said.

The Haitian religious network’s psychosocial program, aided by $83,000 from the Canadian Catholic Organization for Development and Peace, concentrates on Haitians supporting each other — talking through problems with each other in their native Creole.

University student Marguerite Charles credits the Sisters and the psychosocial program for helping her. On Jan. 12 she spent between four and five hours trapped in rubble. When she got out her home was gone.

“There was shock, trauma. I didn’t feel at ease any more.”

Like many Haitians, Charles was afraid to remain indoors for any length of time. The education student now leads a group of teenagers who gather to discuss their experience and their fears. She is passing on the experience of psychological healing she received from the Sisters.

She credits Sr. Matilde Moreno with restoring her confidence so she could go back to university. Moreno led the young people in dances and encouraged them to draw and paint, and then got them talking about their fears.

Edna Genvieve lives in a tent beside her former home with her daughter. At one point she thought she and her daughter would always live in fear.

“After the earthquake, I thought life was over,” she said. “When it rains, I’m still very afraid.”

She was even more afraid for her daughter, who over and over drew pictures of the devil.

“It’s what she was living,” said Genvieve.

Only after her daughter overcame her dread did Genvieve begin to think about the future.

“Slowly, slowly I saw that life was still possible through my daughter — that there still is a future,” she said.

- RAISING UP HAITI -

a Catholic Register special report

Haiti's churches need healing [slideshow]

What now in Haiti?

Post-traumatic stress proves difficult

Catholic aid organizations fly under the radar

Canadian engineer to oversee Haiti’s Church rebuild

Haiti must take this opportunity to change

Crisis makes D&P rethink how it operates

Bold education plan held up by a lack of funds

Church holds community together

D&P-funded program provides pro-life solution to Haiti's sexual violence

Haitians must look to themselves to rebuild their nation

What now in Haiti?

By Michael Swan, The Catholic Register

From inside a brown, battered SUV, with the doors locked and the windows up, and in the company of a seasoned Haitian driver, the Petionville Market after dark is as frightening as any place I’ve ever been.

I have in my time been pushed around and spat on in a back alley in Xian, China. I wandered after dark through Harlem, Times Square, South Bronx and the Bowery in my student days. I’ve crawled over piles of garbage and explored the unlit streets of Nairobi’s slums. I’ve tried photographing the slums of Rio, while the taxi driver yelled at me to get back in the cab. I’ve walked by guards with machetes and automatic rifles to interview people in El Salvador. I’ve questioned people inside homeless shelters and prisons. I’ve been threatened by Toronto drug dealers who didn’t like the presence of a camera on their street.

I’ve had good and sensible reasons to be scared in my career.

But I’ve never been any place where the level of threat was as pervasive and constant as it is in Haiti. I’ve never been in a place that could make me feel afraid while sitting with three other people inside a locked car as it crawled along the street, with a crush of ghostly bodies slipping by our windows in the darkness.

No doubt, pre-earthquake Haiti was a dicey sort of place for outsiders. In 1994 Haitian gang members scared off the U.S. Marines with machetes and stones before America’s elite soldiers had even landed on Haitian soil. The earthquake, I believe, has raised it all up a notch or two.

There’s nothing like the uncertainty of chaos to make us afraid. The piles of rubble, the half-collapsed buildings, the razor wire stretched along sections of cracked and crumbling walls give no indication of order in Haiti’s capital. The market outside Our Lady of the Assumption Cathedral in Port-au-Prince looks like a tidy, predictable, suburban shopping mall compared to the Petionville Market at night, but still every little pile of goods from used auto parts, to cigarettes, to batteries, to discarded office furniture, shoes and on and on looks like contested territory. And every merchant is accompanied by a scowling, oversized partner sizing up each customer who approaches and every non-customer who passes by.

I did not go to Haiti to hear another recap of the shock and distress of Jan. 12, 2010. Of course I spoke to people who lost their children, their grandfathers, their wives and their husbands. I spoke to a young woman who spent five hours trapped in the rubble.

I also spoke to peasant farmers as they were recovering from torrential rain brought by Hurricane Tomas — hours and hours huddled under a sheet of tin where their house used to be, as rain threatened to wash away everything. Then they reached back 10 months and told me about the terror of seeing their houses collapse and walking to Port-au-Prince to search for their families.

“While we were walking to Port-au-Prince we had to walk around cadavers,” said Fritz Ner-Sérénium.

With 230,000 dead, more than half of Port-au-Prince still in ruins, over a million people still living under tarpaulins or in tents, there are far too many of those stories to even begin. And repetition adds little in the way of insight.

The Catholic Register wanted to know, what now? After a year, what has happened and what direction is Haiti taking?

If there were a simple, definite answer the question wouldn’t be worth asking. Journalists ask questions that have more than one answer because multiple, even conflicting answers are closer to the truth of a complex world.

But some truths are unambiguous. One of them is that 10 months living in a tent is hard.

Redemptorist Fr. Adonai Jean-Juste sat with me on a bench in the midst of what used to be his home staring straight ahead, hardly able to gather the energy to answer questions.

“Living in the tent is not easy. I want to get out of the tents. It’s too much for me now, living in the tents,” he said.

A construction crew of five men was busy on the other side of the line of tents where four Redemptorists live, mixing cement, piling up rebar, getting ready to start rebuilding the walls that will house the four religious — two men studying for priesthood, a brother and their superior Jean-Juste.

“I see the presence of God in the earthquake. Many people died. Many, many people died. We didn’t have the means to bury them,” he said. “But everyone was living in the open air and it didn’t rain. That was a surprise. I think God was with other people who died. I think maybe it was His will. It was their time.”

Haitians are the world champions of the brave face. They make British stiff upper lips look look wobbly as Jello.

The Missionary Sisters of the Immaculate Conception are all business — entirely consumed by their mission to educate the girls and rebuild the school. Meanwhile the nine sisters are living in four tiny classrooms, their possessions piled up in an old box car, praying the morning office in a crowded little corner next to the one sink they all share. They spend all day outside under the cruel gaze of the Caribbean sun or under the Unicef tarpaulins where they teach 40 girls at a time.

They will only talk about the school, the girls, the community. The closest they come to talking about themselves is when Sr. Josette Drouinard lets slip her dream that one day the students will have a chapel and auditorium — some beauty in their lives and not just dust and desks and sun. She doesn’t say that she and her sisters could use a refuge for prayer.

Downtown St. Antoine’s school principal Sr. Saint Anne Jean-Baptiste answered my questions with that same distant stare and weariness as Jean-Just. Except that in the sister’s case no cement is being mixed, no plans are being spread on a wobbly table under another patch of tarp, no promises have been made that the Sisters of St. Anne will have their own school again.

We tried to hide from the sun in the only bare sliver of shade available, while the students in their pink dresses dart around us and line up for lunch.

Jean-Baptiste allows it is a “difficult situation.”

My notes are full of sentences that begin with “no.”

“No office.”

“No space to work with students.”

“No land to build a new school.”

“Not getting enough school hours.” (Students that is, whom she fears for the first time in St. Antoine’s history may not pass the state exam that qualifies them to go on to Grade 7.)

“We have so many needs, it’s overwhelming,” she said.

But each and every Haitian has a memory from the earthquake that doesn’t fill them with horror or overwhelming sadness. After the earthquake Haitians stood together atop the rubble and dug. They moved hunks of concrete together, passing the pieces of their former city from hand to hand. Haitians were together. They cared for one another.

“It brought people together. There was solidarity,” said Yolette Jeanty.

That concrete memory of post-earthquake Haiti stripped down to it’s core, when Haitians had nothing but each other, is not a memory of violence or greed or humiliations or vengeance. For lack of any better word, it is a memory of love — true love, not sentimentality. It was the love that binds us together and makes society possible. It is the love that makes God present and promises a future.

- RAISING UP HAITI -

a Catholic Register special report

Haiti's churches need healing [slideshow]

What now in Haiti?

Post-traumatic stress proves difficult

Catholic aid organizations fly under the radar

Canadian engineer to oversee Haiti’s Church rebuild

Haiti must take this opportunity to change

Crisis makes D&P rethink how it operates

Bold education plan held up by a lack of funds

Church holds community together

D&P-funded program provides pro-life solution to Haiti's sexual violence

Haitians must look to themselves to rebuild their nation

Raising up Haiti: A Catholic Register Special Report

By Catholic Register Staff On the anniversary of the 7.0 magnitude Haiti earthquake that killed 230,000 people, The Catholic Register has compiled a special report on reconstruction efforts in the impoverished nation.

On the anniversary of the 7.0 magnitude Haiti earthquake that killed 230,000 people, The Catholic Register has compiled a special report on reconstruction efforts in the impoverished nation.

At 4:53 p.m. on Jan. 12, 2010, Haiti was devastated. The quake’s epicentre was 16 km west of the capital of Port-au-Prince, home to 3.5-million people. Large sections of the city were flattened and virtually every building damaged. Hospitals, schools and government buildings collapsed on their inhabitants. The city’s cathedral crumbled, killing Archbishop Joseph Serge Miot. An estimated 1.5-million people were made homeless.

The international community sent emergency supplies, money and manpower, and pledged $5.3 billion for long-term reconstruction. Canadian Catholics contributed more than $20 million to Haitian relief.

To mark the first anniversary of the quake, The Register dispatched Associate Editor Michael Swan to Haiti to document the reconstruction effort. He saw a nation still clearing rubble from streets, still coping with tent cities, still flinching from crime, still living day to day. The rebuilding has begun but it is sporadic and not always well co-ordinated.

But The Register’s veteran reporter also witnessed hope and resilience and even some joy.

“Haitians are the world champions of the brave face,” he writes. “They make British stiff upper lips look wobbly as Jello.”

One year on, we should pause to remember Haiti. Its needs remain great. In the articles listed below, Swan tells Haiti’s story in words and photos.

- RAISING UP HAITI -

a Catholic Register special report

Haiti's churches need healing [slideshow]

What now in Haiti?

Post-traumatic stress proves difficult

Catholic aid organizations fly under the radar

Canadian engineer to oversee Haiti’s Church rebuild

Haiti must take this opportunity to change

Crisis makes D&P rethink how it operates

Bold education plan held up by a lack of funds

Church holds community together

D&P-funded program provides pro-life solution to Haiti's sexual violence

Haitians must look to themselves to rebuild their nation

The year in review - The people and places of 2010

By Catholic Register StaffCanadians united behind St. Brother André in 2010

In a year with much doom and gloom, from the devastating Haiti earthquake to the massacre of Catholics at a Baghdad church, Canadians can look back with pride on one event that brought abundant joy — the canonization of Montreal's St. Brother André.

In a year with much doom and gloom, from the devastating Haiti earthquake to the massacre of Catholics at a Baghdad church, Canadians can look back with pride on one event that brought abundant joy — the canonization of Montreal's St. Brother André.St. Brother André is only the second Canadian-born saint, the first male, joining St. Marguerite d'Youville who was canonized in 1990. He was Catholic Canada's story of the year.

The former doorman at Montreal's Notre Dame College and founder of St. Joseph's Oratory was elevated to sainthood by Pope Benedict XVI on Oct. 17. Some 5,000 Canadians were in the crowd of 50,000 at St. Peter's Square while thousands more came to the Oratory to mark the occasion.

Among the St. Peter's crowd was a 19-year-old Quebec man whose unexplainable cure from a cranial trauma was recognized by the Vatican as the second miracle directly attributed to St. Brother André. The man, who emerged from what doctors had called an irreversible coma at age nine, has always guarded his privacy and remains anonymous to this day.

André Bessette was a poor, illiterate orphan who, after moving between several menial jobs, was accepted by the Congregation of Holy Cross in Montreal where he lived a remarkable life of faith, hope and charity. He spent countless hours ministering to the sick and lonely and his devotion to St. Joseph and his reputation for healing attracted thousands of people. He is credited with thousands of miraculous healings and, through his determined efforts, became the driving force behind construction of the spectacular St. Joseph’s Oratory in Montreal, which draws upwards of two million visitors annually.

Anyone who walks into the Oratory can see the racks of canes and crutches stretching up the walls — hardwood evidence of the miraculous cures brought about by St. Brother André’s prayers. He freed people of pain and suffering with oil collected from under a candle in front of a statue of St. Joseph, with holy medals and with prayers — though he never looked upon himself as a healer.

The canonization made front-page news across Canada, not only in the religious press, but also in the nation's largest secular newspapers.

But perhaps most important, St. Brother André's canonization brought faith back into the equation in his native Quebec, a province that had turned its back on the Catholic Church during the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s. Now there are those who believe Quebec may be ready to rediscover a different side of its Catholic roots.

"Now people are talking more about Brother André because of the canonization," said Fr. Claude Grou, director of the Oratory. "There is a fascination with the person of Brother André."

A younger generation of Quebeckers has a more open attitude to Brother André than those whose political consciousness and cultural attitudes were formed by the Quiet Revolution, said Grou.

“Starting with people in the media — outside the Catholic media — many of the younger people I talk to are a little more sensitive,” said Grou. “They have not known the revolution of 1960, the Quiet Revolution. Their parents have known that. They have a fascination with some of the things that have been pushed aside in the past. They show a new interest.”

This interest shows in the revival of a pilgrimage to the saint's hometown of Mont Saint-Gregoire. For years the pilgrimage from the Oratory had been popular but its numbers had slowly dwindled until it was finally cancelled. But the pilgrimage was revived this year, taking place on St. Brother André's birthday, Aug. 29.

The Church will mark St. Brother André's feast day on Jan. 6.

Year in review

January

January

- A devastating earthquake ravages Haiti, killing upwards of 200,000 and displacing millions. Catholics immediately join in relief efforts and contribute to more than $100 million raised across Canada.

- Toronto welcomes its two newest bishops — Bishop Vincent Nguyen and Bishop William McGrattan.

- The diocese of Antigonish is off to a new start with the installation of Bishop Brian Dunn. The diocese has been caught up in scandal surrounding the arrest of Dunn's predecessor, Bishop Raymond Lahey, on child pornography charges.

February

February

- Vancouver welcomes the world to the Winter Olympic Games, with the archdiocese of Vancouver showing its "radical hospitality" to the world's visitors.

- The Vatican hosts a two-day summit on the widening Irish sex abuse scandal. Pope Benedict XVI notes the "errors of judgment and omission" that fuelled the crisis.

- Church and pro-life leaders condemn Liberal Leader Michael Ignatieff for advocating Canada fund overseas abortions to "improve" women's health care.

March

March

- Anglican groups worldwide, including in Canada, seek union with the Catholic Church, responding to the Pope's offer to come into communion with the Church.

- Bloc Quebecois MP Francine Lalonde reintroduces her euthanasia bill in the House of Commons. It is later defeated.

- Toronto Archbishop Thomas Collins, in addressing the world wide abuse scandal facing the Church, says while it is a challenge, it is also an opportunity to refocus on the baptismal call to live out the Gospel teachings.

April

April

- Bishop James Wingle offers his surprise resignation as bishop of the diocese of St. Catharines, Ont., citing stamina issues.

- Archbishop Thomas Collins announces a review of the archdiocese's abuse protocols in the wake of the worldwide abuse scandal.

- The British Petroleum oil spill brings an ecological and economic disaster to the Gulf of Mexico and surrounding regions. The Catholic Church is quick to provide aid to those affected.

May

May

- Pope Benedict XVI visits Portugal and the Marian shrine in Fatima amid concerns that one of Europe's most Catholic countries is losing its faith.

- Toronto faith leaders meet with candidates vying for the mayor's seat. The candidates give their thoughts on how they could work with faith groups.

- Quebec's Cardinal Marc Ouellet is pilloried in the national media for calling abortion a moral crime at a Quebec City pro-life conference.

June

June

- The G8 and G20 Summits take centre stage in Toronto and area. Key among the agreements is the "Muskoka Initiative," a pledge of $7.3 billion to reduce maternal and child deaths.

- Fr. Jerzy Popieluszko, a Polish priest who was murdered for standing up against communism, is beatified.

- A sacred-fire ceremony in Winnipeg kicks off the first national event for Indian residential schools survivors as part of the national Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

July

July

- Cuban Church leaders are key in obtaining the release of 52 political prisoners in the communist nation.

- Archbishop Thomas Collins pushes Canada's bishops to help Iraqi refugees flee persecution in the region. He leads by example by sponsoring a family himself.

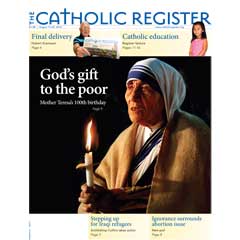

- To mark the 100th anniversary of the birth of Mother Teresa, a number of her relics tour parishes across Canada.

August

August

- Toronto Catholic District School Board chair Angela Kennedy is found guilty of conflict-of-interest charges for voting on a matter that would affect her children who are employed at the board.

- Cardinal Marc Ouellet is off to Rome where he assumes his new role as Prefect of the Congregation for Bishops at the Vatican.

- A public outcry greets news that a Muslim group plans to build an Islamic community centre just steps from the World Trade Centre site in New York.

September

September

- Pope Benedict makes a historic visit to Great Britain where he beatifies Cardinal John Henry Newman.

- After donations came up short in 2009, ShareLife announces a record year in 2010, with Catholics showing their generosity in donating $14.33 million.

- Big changes are announced for the Hamilton diocese. After 26 years as the diocese's bishop, Anthony Tonnos retires and is replaced by Bishop Douglas Crosby.

October

October

- A pro-life demonstration on the Carleton University campus ends when Ottawa police arrest four members of Carleton Lifeline.

- The archdiocese of Toronto releases its new abuse protocols, making them more clear and expanded to include all lay employees and volunteers.

- A terrorist attack on a Baghdad church leaves 58 dead and scores more wounded. It comes just days after the close of the Synod of Bishops for the Middle East, which had discussed protection of Christians in the Middle East.

November

November

- Adding to the woes of Haiti as it recovers from the devastating earthquake, a cholera epidemic strikes, killing more than 1,000 and rising.

- The Canadian Catholic Organization for Development and Peace fine tunes its funding protocols to make sure none of its funding ends up in pro-abortion groups' hands.

- St. Francis Table in Toronto's Parkdale area serves up its one-millionth meal since opening to feed the poor in 1987.

December

December

- Immigration Minister Jason Kenney lashes out at Canada's Catholic bishops for criticizing his anti-human-smuggling bill.

- The Vatican gets stung in diplomatic cables released by WikiLeaks. A wide range of issues are touched on, including the Irish abuse scandal.

- For the sixth year in a row, the creche scene outside of Toronto's Old City Hall is vandalized. The creche is set up by Gethsemene Ministries each year.

Ruth Lobo’s pro-life passion stems from her own origins

By Deborah Gyapong, Canadian Catholic News OTTAWA - Ruth Lobo’s commitment to the pro-life cause is a deeply personal one that began 23 years ago in her native India.

OTTAWA - Ruth Lobo’s commitment to the pro-life cause is a deeply personal one that began 23 years ago in her native India.All Lobo knows about her birth mother is that she was 19, most likely poor and “most likely ostracized by her family for being pregnant.” She sought shelter in a Bangalore convent that provided help for single mothers. She looked after Lobo for three months before giving her up to a woman who would become her adoptive aunt.