An Angus Reid Institute poll for the Faith In Canada 150 project of the Cardus think tank found half of Canadians are ambivalent on the subject of a papal apology for residential schools, saying it would be “somewhat meaningful — it would make a difference, but so would a lot of other things.”

Another 29 per cent said an apology would be “very meaningful” and 21 per cent said “not meaningful at all.”

That kind of result just won’t do for Aboriginal Catholics like Deacon Rennie Nahanee, an elder of the Squamish First Nation in British Columbia and head of First Nations Ministry for the Archdiocese of Vancouver.

“Certainly to me as an Indigenous person, it would mean a lot,” said Nahanee.

Nahanee did not attend a residential school, but his parents and all his older siblings did. Their formation inside an institution whose purpose was to erase Native Canadian language, culture and tradition shaped his family life and his entire community.

Nahanee is well aware of the many apologies offered in Canada over the last 25 years by individual religious orders, dioceses, Catholic institutions who ran the schools on behalf of the government of Canada. But Aboriginal Catholics need to hear their Church speak with one voice, Nahanee said.

“So all these apologies come from separate areas,” said Nahanee. “Something from the Holy Father about that, spoken to the Indigenous people — and if he should come here — it would mean a whole lot to those who have suffered and died, and to those who are still suffering and living.”

In a 2009 meeting at the Vatican, Pope Benedict XVI apologized to a delegation of native leaders under Phil Fontaine, former National Chief of the Assembly of First Nations, for the suffering of Native Canadians in Church-run residential schools. Fontaine had sought an apology from the Pope following one issued by former Prime Minister Stephen Harper.

(Graphic by Erik Canaria)

(Graphic by Erik Canaria)

“We were looking for a similar apology from the Catholic Church, and I was a witness to that today,” Fontaine said at the time. Native leaders “heard what we came here for.”

“We wanted to hear him (Pope Benedict) say that he understands and that he is sorry and that he feels our suffering — and we heard that very clearly.”

A papal apology on Canadian soil would hold much more significance among Indigenous Canadians than Harper’s 2008 apology on behalf of Canada, said Nahanee.

“I think they would believe the Holy Father more than they did Prime Minister Harper,” he said.

There’s much more to the history of Aboriginal Canadians, the Church and colonization than just residential schools, said Malaseet elder and former Lieutenant Governor of New Brunswick Graydon Nicholas.

“It didn’t just start a few years ago,” said Nicholas. “You have to go back to 1490 when the Pope (Alexander VI) divided the world into two parts and generously gave half to the Portuguese and half to the Spanish (the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas). There was a very generous pope. Nobody bothered to ask the Indigenous people if this was all right.”

Nicholas is amazed some Catholics question the need for a papal apology on Canadian soil to Aboriginal Canadians but never questioned Pope Benedict XVI’s 2010 apology in Ireland for sexual and physical abuse by clergy and religious.

“There’s a double standard here,” Nicholas said. “You can do it for the Irish, but for us it’s, ‘What more do they want?’ ”

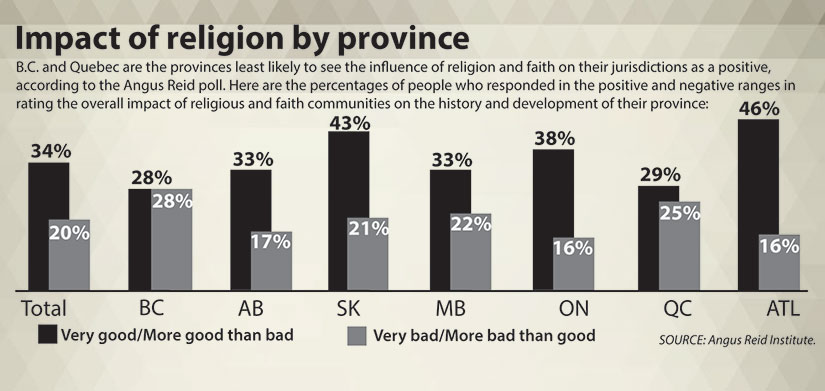

Residential schools and reconciliation between native and non-native Canadians was almost the only negative in a set of survey results that showed most Canadians view faith as a positive in their communities. Asked whether local faith-based institutions are a boon or a burden, the majority responded positively.

Over half of survey respondents rated faith-based social services “very positive,” compared with just six per cent who ranked them “very negative.”

When it comes to residential schools, only nine per cent of Canadians regard Church involvement as “very positive,” versus 58 per cent who say it was “very negative.”

Angus Reid conducted its online survey June 14-19 among 1,504 adults. The poll is considered accurate to within plus or minus 2.5 per cent, 19 times out of 20.