But he has gone far beyond being just a survivor; he is actively plotting a path that he hopes will help the government and First Nations leaders not just understand the past, but plan for the future.

The former chief of the Cowessess First Nation has been awarded a three-year, $150,000 Vanier scholarship by the University of Saskatchewan to further his PhD research into the relationship between residential schools, the government and the leadership in the Indigenous community. Vanier scholarships are awarded through a federal program to help universities attract doctoral students.

“I’m saying that residential schools and Indian Affairs (now Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada), combined through their bureaucracy and their rules and their training, shaped the ethical behaviour of our leadership,” said Pelletier, 61, who was a student of Marieval Indian Residential School in Saskatchewan from 1960 to 1968.

The residential school system began in the late 19th century and reached its peak in the 1930s before dying out in the 1990s. The schools, funded by the government and run by churches, have been widely discredited for being sites of abuse and for robbing Indigenous children of their culture.

Once Pelletier completes his doctorate research, he hopes to present it to the government just as he has with numerous other community research projects, including his work on the 2013 Joint Task Force in Saskatchewan involving 16 First Nations schools.

“Already in the last 10 or 12 years that I’ve been involved with graduate studies, we’ve done many reports for the government in terms of policy analysis to help them to make good decisions for Aboriginal people,” said Pelletier, who is also an educator with the university’s Indian Teacher Education Program (ITEP).

Pelletier believes those in authority, from elected government officials to local chiefs on reserves, continue to make decisions rooted in self-interest rather than the community.

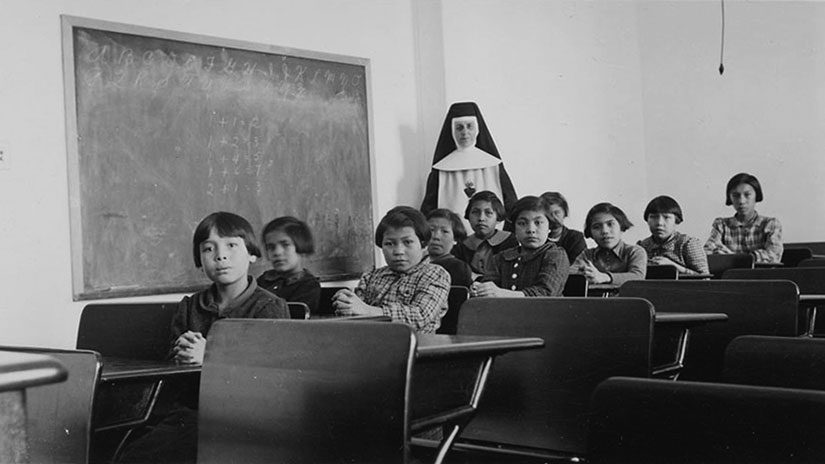

In this 1940 photo, a group of female students and a nun pose in a classroom at Cross Lake Indian Residential School in Manitoba. (CNS photo/Library and Archives Canada, Reuters)

In this 1940 photo, a group of female students and a nun pose in a classroom at Cross Lake Indian Residential School in Manitoba. (CNS photo/Library and Archives Canada, Reuters)

“The capitalist way of leading is a dog-eat-dog approach,” he said. “The system today shapes you to be like that. You have to think a little bigger than that. ... We have to have people with big vision.”

At the heart of the indoctrinated ethics forced upon First Nations people is capitalism and democracy, said Pelletier. Although both have become synonymous with freedom in the western world, Pelletier said these philosophies act as an “iron cage on our minds” of First Nations.

“Residential school was more like a warehouse for kids as far as I’m concerned,” he said. “It was like being trained to take orders and to fit the institution.”

This training “to be a good little Indian” left First Nations unprepared for life, said Pelletier, who also blames residential schools for contributing to the death of three siblings, two by suicide.

Even today, he sees the oppressive effects of the residential school on the Indigenous youth.

“They are right in my class,” he said. “They complain about the harnesses that they have to work with when they try to deliver quality education to the kids. I tell them simply that that structure is not going to change, Indian Affairs is not going to change (and) the chief and counsel management system is not going to change.”

But Pelletier is no pessimist.

“(So) what I try to teach them in the classroom is that there are more, there are other, methods of leading besides the ones that are put out by western thought or theory,” he said. “What I’m trying to do here is instil some sense of leadership ethics that is not a capitalistic point of view based on capitalistic greed.”

Pelletier is also aware one man’s voice is not enough.

“We all have to be out there to encourage that, to model that and to put together leadership models that people can follow,” he said. “Indian Affairs continues to, along with the residential school upbringing of people from my generation, keep us from moving on. They are institutions, for God’s sake, that were set up to oppress Indians and keep them on the reserves while the West was settled.”