The moon of course — and the entire vastness of the universe — is as much a part of creation as the Earth itself. Heaven — communion with God in the company of the saints — is not a place on the moon or the planets or the stars. Yet the lunar missions were treated as a metaphor — perhaps more than that — for man’s aspiration to reach God in His Heaven. In his famous phone call 50 years ago to the astronauts on the moon, President Richard Nixon put it in just those terms.

“Because of what you have done, the heavens have become a part of man’s world,” Nixon said. “And as you talk to us from the Sea of Tranquility, it inspires us to redouble our efforts to bring peace and tranquility to Earth.”

Read literally, there is a touch of salvation-by-our-means to that, as if we could capture Heaven and bring it to Earth. But Nixon was using the “heavens” here in its double sense, that of the astronomical, “celestial” bodies, and that of the realm of the blessed.

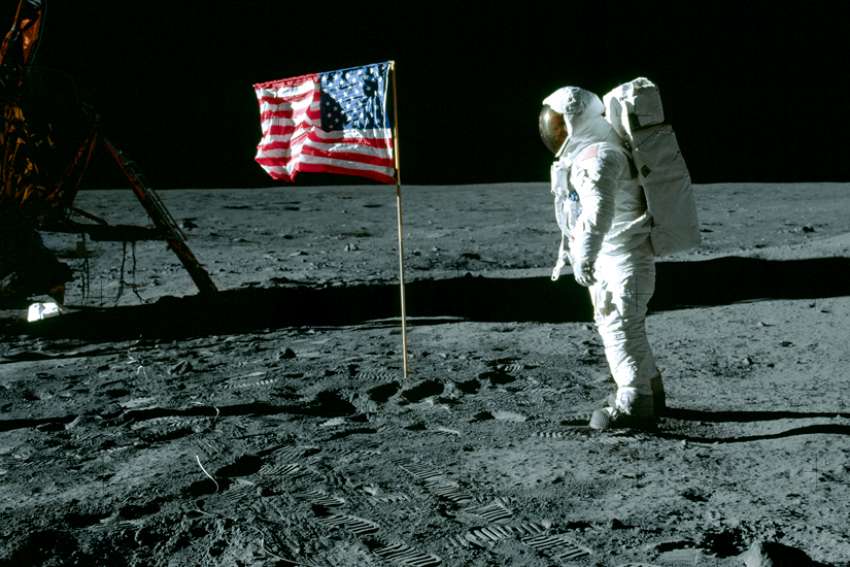

On the 50th anniversary of the lunar landing — July 20, 1969 — I visited a special Apollo 11 exhibition here at the Nixon Presidential Library. While we associate the Apollo program with JFK’s 1961 promise of “landing a man on the moon and returning him safely,” it was actually Nixon who was a new president when it happened. Hence the Nixon archives have some fascinating details about Apollo 11.

One of the most remarkable items in the exhibition is a memorandum from William Safire, the presidential speechwriter, to Nixon’s chief of staff, H. R. Haldeman. Discovered only in 1999, it contained a speech written for Nixon entitled “In Event of Moon Disaster.”

The memorandum suggested plans for what should be done if the astronauts on the lunar surface could not return to their orbiting spacecraft. They would be marooned on the moon to die. The president would call the “widows-to-be” first, and then a clergyman would lead the rituals used when sailors are to be buried at sea. Then Nixon would address the nation.

“Fate has ordained that the men who went to the moon to explore in peace will stay on the moon to rest in peace,” Nixon would have begun. “These brave men, Neil Armstrong and Edwin Aldrin, know that there is no hope for their recovery. But they also know that there is hope for mankind in their sacrifice.

“In ancient days, men looked at stars and saw their heroes in the constellations,” the proposed text continued. “In modern times, we do much the same, but our heroes are epic men of flesh and blood. … For every human being who looks up at the moon in the nights to come will know that there is some corner of another world that is forever mankind.”

It is a deeply biblical point of view. The presence of the dead somehow consecrates the land of their burial to their cause and identity. I don’t know whether Safire had Abraham in mind when he wrote those lines, but he was a Jew who knew his Scriptures well.

Consciously or not, the insistence by Abraham that he buy a plot in the promised land in which to bury his wife Sarah finds an echo in Safire’s draft. Abraham stakes his claim to the promised land with a grave.

The same principle is at work in our famous war graves. The Canadian soldiers who died at Normandy are buried in land granted by France to Canada. The dead have claimed that land by their sacrifice.

And so, Safire proposed, the soon-to-die astronauts on the moon would extend man’s place, his claim. Where they would lie would be another place, distant from home, that would be “forever mankind.”

All of which is given its proper theological depth on the solemn feast of the Assumption which falls on Aug. 15. The Assumption is the dogma of faith that the Mother of God was assumed bodily into Heaven. One like us is in Heaven; part of Heaven is therefore “forever mankind.”

Where Mary has gone, we hope to follow. The collect for the Mass of the Assumption puts it this way: “She was crowned this day with surpassing glory; grant through her prayers, that, saved by the mystery of Your redemption, we may merit to be exalted by You on high.”

There is of course a key difference. What was claimed — by Sarah, by fallen soldiers, potentially by astronauts — in death is now claimed in life. The Risen Jesus leaves the tomb empty. For His Mother, He gives the privilege of no tomb at all.

And she is our mother too, where in eternal life she, following her Son, has claimed a place for mankind in Heaven.

(Fr. de Souza is editor-in-chief of Convivium.ca and a pastor in the Archdiocese of Kingston.)