It’s an occasion for gratitude, for this American immigrant has become a treasure of the Church in Canada, if a largely hidden one. That’s suitable enough for a son of St. Philip; part of their charism is amare nesceri — a love of being unknown or hidden.

Pearson has taught at St. Philip’s Seminary his entire priesthood, which is one reason for that hiddenness. It’s where I studied philosophy back when Pearson was not even 10 years ordained, and so I and my fellow seminarians over these many years know well his gifts as a teacher of Catholic philosophy and theology. Yet we only number in the hundreds, as opposed to, say, the thousands who might be a large Toronto parish on a typical Sunday.

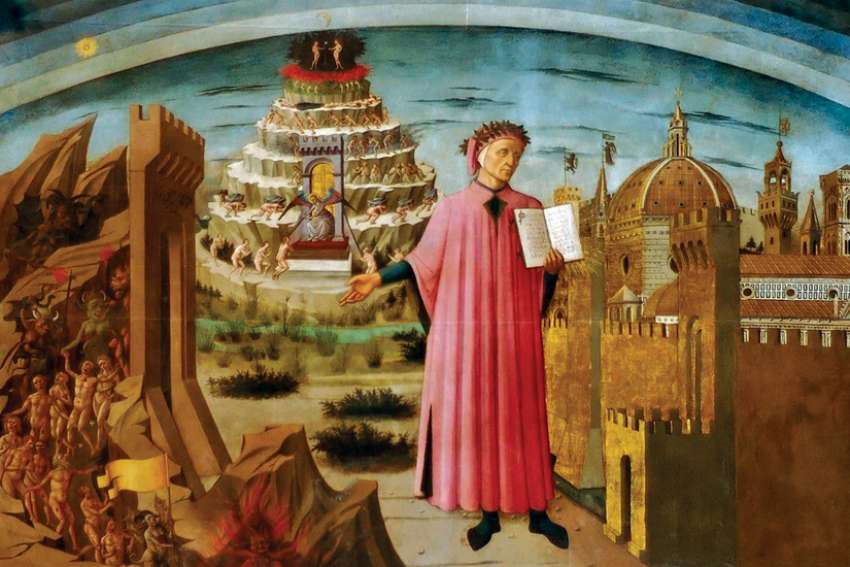

Now those gifts are available to a wider audience, for he has published what really is an extraordinary book. Spiritual Direction from Dante: Avoiding the Inferno (TAN Books) is the fruit of Pearson’s many years leading a seminar on the Divine Comedy for his seminarian students.

The book is extraordinary not only in the sense that it is very well done, but because it is not the usual treatment of Dante as a work of literary magnificence, or even philosophical and theological depth. Pearson treats the Inferno — volumes on the Purgatorio and Paradiso are forthcoming — as a repository of spiritual wisdom for the life of disciples. Dante’s guided tour of hell is meant to help his readers avoid it.

“He who does not go down into hell while he is alive, runs a great risk of going there after he is dead,” Pearson quotes St. Philip. The 16th-century founder and spiritual master likely read Dante, the principal adornment of Italian literature, and perhaps got that insight from the Inferno.

For Pearson, Dante’s key insight is that sin is its own punishment, namely that sin not only damages our relationship with God, but diminishes us. The punishments that Dante conjures for sinners in hell are a visible manifestation of the damage that sin has already done to them.

So, for example, those guilty of simony — profiting from the sale of the sacraments — are buried upside-down, for they have inverted the proper order of things, putting sacred things to profane use. Their exposed feet are burned by descending flames, an inversion of Pentecost; the Spirit comes not to illumine the mind but to burn the feet.

“Dante is convinced that the sufferings of hell are really just a distillation or permanent snapshot of the natural byproducts of sin, side effects we already begin to experience here in this life,” Pearson writes. “What we see there is a revelation of the true nature of sin, once its alluring disguise is stripped away. As a result, Inferno is not merely about (the damned); it is about us. And it is not only about the way we might be some day; it reveals the way we are right now.”

Those who have benefitted for many years from Pearson’s teaching and spiritual direction will recognize the distilled wisdom there of Catholic anthropology, or our understanding of the human person. It was perhaps most famously expressed by the Second Vatican Council’s teaching that Jesus Christ not only reveals God to man, but also man to himself.

The wisdom of Dante interpreted and made accessible by Pearson makes an important and needed contribution to our approach to moral theology. It’s a gross simplification, but we might say that a century ago Catholic moral theology was about knowing the rules as taught by the Church and applying them correctly. In recent decades the renewal called for by Vatican II shifted the emphasis to how our relationship with the Lord Jesus is lived out in our moral choices. Our desire to conform ourselves to Christ thus shapes our moral decisions; we act a certain way because of who we already are in Christ.

All to the good, but the flipside has been forgotten, namely that while grace conforms us to Christ Jesus, sin also conforms us — or better to say, deforms us. The widely remarked loss of a sense of sin — including among those pastors who think it better to leave people in their sins as conversion might be too difficult — is partly due to forgetting that sin is bad for us here and now, independent of God. Not entirely independent of God of course; sin is bad for us because God did not create us for sin, but for holiness, for Himself.

Pearson’s Inferno-inspired spiritual direction is therefore a necessary correction, or an act of remembering the long tradition of which Dante is — to use one of the Divine Comedy’s favourite images — one of the brightest stars.

The book is dedicated to the seminarians Pearson has taught. From me, on their behalf — Ad Multos Annos!

(Fr. de Souza is editor-in-chief of Convivium.ca and a pastor in the Archdiocese of Kingston.)